Watching time pass by?

I don’t know about you, but I inevitably think of time passing when we chime in the New Year. That said, I’m definitely not one who musters up new year’s resolutions. But the changing a digit of the year, i.e. when I have to fill in the date on a form, makes for a cognitive wake-up, if not a shake-up. At the end of the day, new year’s day is just another day, albeit made with a lot of fanfare and midnight noise. It makes me think of the funny remark some have about how time is passing by so fast. I’m sure you’ve heard someone say as they sit watching over or talking about their kids: “I don’t know where the time has gone!” I believe that time passes in accordance with how we live. The more we are present, the more time is one our side. On the other hand, if we live our lives fretting about the future, or regretting the past, it’s sure to have an effect on our impression of time. In our society today, between a heightened sense of self-worth, diminishing religious affiliations and improvements in technology, there’s a growing interest in the ability to move beyond death. Whereas religion has always served as man’s greatest response to death, without it, we no longer have a satisfactory answer as to what happens once the body dies. As there’s a burgeoning sense of entitlement and the technology seems available, funds and energies are being ploughed at unprecedented levels into a quest for immortality. If you’ve read Matt Haig’s book, “How to Stop Time,” the dream would be to develop the “rare disease of immortality” suffered by the main protagonist, Tom Hazard. Today, there’s a fanciful surge of interest in curing aging as if it were a disease, with others seeking to eliminate death. In this article, I’d like to review this trend for longevity and eternity, and suggest we’d be better off putting our energies to other areas, such as figuring out how to make democracy work, deal with the basics of healthcare, seed more empathy in society, and rehabilitate values of community and sacrifice.

When progress turns to hubris

There is, in the human condition, two interesting drivers. First, a need to analyse, codify and dominate things around us (science) and, secondly, a hunt for progress (expressed as ambition). In each, there is a tremendously positive force. But, taken too far, there is always going to be danger. We develop a sense of self-worth and power through advancement. For example, we are constantly looking to tame nature (e.g. ways to change the weather) and to make faster, better animals, plants and machines, such as with GMOs and artificial intelligence. It inevitably tumbles into hubris. In the face of an explosion of artificial intelligence that are moving inexorably closer to life forms, it’s only natural, some might posit, that human beings will seek an artificial existence. With the background of sprouting AI and a foreground of spiralling mental health, the current human story seems on the verge of becoming unhinged. There is no greater example of the derailment of humanity than the burgeoning quest for everlasting life. It’s tantamount to a request for divinity, with the irony being that those who are most interested in this are not religious. Or perhaps it’s come about precisely because they aren’t religious and, therefore, don’t have a God-given answer to what happens after death. This is the fundamental story of the avatar trap, about which I have written before, where we try to escape the human condition to create an alternative reality, one where we imagine ourselves as perfect, godlike beings.

An eternal quest

Granted the ideas of eternal youth and immortality have preyed on people’s minds going back many centuries, most notably in the story of Calypso (image source), featured in the Greek epic written by Homer, who offered immortality to Odysseus in return for his company. But, these days, the way some people are talking about defying death and curing aging, it seems that there are many genuine believers. It’s another area where Silicon Valley is happy to push through the limits, in view of a limitless life. Many strains of society are keen to remove all limits. Concepts of discipline, commitment and rules are all malleable. Kids are given innumerable, unending and ultimately unappreciated presents at Christmas. They are handed grades of over 100%. They are hallowed for good effort after finishing last in the race. They’re allowed to feel whatever they wish and identify however they want. They are encouraged to believe the sky’s no limit and to dream big. However, I’m not sure that such beliefs and practices set us up for resilience and an ability to overcome life’s inevitable challenges.

The business of life… everlasting

In the world of cosmetics, there’s always been a pretty penny to make with anti-aging creams and potions. Apparently, the Egyptian queen, Cleopatra, famously enjoyed having daily donkey-milk baths, requiring over 700 donkeys to accomplish each time. {Source} Today, more prosaically, the anti-aging cosmetic market, according to Custom Market Insights (CMI), was estimated at a plum $60 billion in 2021. And it’s expected to double in just nine years, to reach c. $120 billion by 2030, led by the likes of L’Oréal, Estée Lauder and Beiersdorf. {Source} By the same token, Man’s wish to live forever goes back a long while too; to wit you will find a slew of books with the title, “Man’s Search of Immortality,” documenting our long interest in the topic. Today, Precision Reports wrote that the global longevity and anti-senescence therapy market size is projected to reach $566 million by 2028, from $318 million in 2021. {Source} I note that both this industry and the anti-aging cosmetics industry carry the same projected compound annual growth rates (CAGR) of 8%. But the quest of longevity, getting rid of old age, and the hope for eternal life are deeply flawed concepts. They speak to an outlandish and widespread narcissism, an implausible world condition and, most saliently, a complete misunderstanding of life. As Viktor Frankl wrote in his gem of a book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” life is about making sense of our short passage on Earth. As the folk tale that gave rise to the name of the psychedelic rock band that I’ve followed for many decades, The Grateful Dead, once you embrace your mortality, you will appreciate better your life in the now. Without even attempting to imagine whether these longevity funds and research centres have entertained if it’s better we all stayed the same age or just got older without dying, let me lay out the reasons why I find the quest for this “holy grail” as an errant and, worse, unhealthy fool’s errand. It’s quite obvious that people striving for immortality have not thought through the unintended — much less obvious — consequences of a world full of immortal human beings.

(1) First mover advantage to hold on to power

Let me lay out a pretty picture. Just say, for example, the miracle “cure” happened tomorrow. It’s likely that the people with experience and already in power will be best suited to continue ruling, no? In any event, they might find less good reason to stand down. We could end up with Trumps and Bidens competing against other … forever? And, anyway, who will be the arbiter of who gets what? In a world where the divide between the have and the have nots is getting wider, access to any death-defying remedies at first will surely be the privilege of the uber wealthy. So, to any extent the money flowing into this industry were successful, it’s likely to be the dominion of a very small group… potentially fulfilling their demi-god status and making only them immortal. And those who first gain access to this potent potion will likely have a first-mover advantage in that they will also wish to control its spread. As with pretty much every dystopian world view, the people wielding the power are typically a select (and distorted) few, e.g. the Elders in “The Giver”, ten world controllers in “Brave New World” or Big Brother in “1984.” The ones to become the first ever immortal human beings would likely wield a power that they’d surely not wish to give up. There is a list of marquee billionaires including Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel who’ve bought into the pipe dream that 90 is the new 50… I think it’s worth noting how it’s a list dominated by men. I also highlight a less well-known tech entrepreneur, Bryan Johnson, currently 47, who has been paying $2 million/year for, amongst other actions, getting infusions of blood plasma from his son {Source: The Guardian}. One gets the distinct impression that none of these entrepreneurs are actually doing these investments for the benefit of the world. The intended beneficiary is inevitably the self. The ‘chosen’ immortals, should they ever reach their Valhalla, will likely fall into the role of everlasting dictators. And, as we know, once a dictator gets into position, he is not wont to let go of that power {think: Putin, Bashar al-Assad, Kim Jung-Un and probably Xi…}. So, once the elixir is unlocked, will the first movers relinquish control? And to whom would it be allocated?

(2) History can repeat itself

I am reminded of the story of the Kykeon, a mythical mixture of natural ingredients with psychedelic properties that used to be doled out to the masses thousands of years ago, notably in Ancient Greece. It was said that Elysium, home of the blessed after death, promised the likes of Plato immortality by drinking the potion and seeing god. As recounted by Brian C. Muraresku, a lawyer and classicist, in his acclaimed book, “The Immortality Key,” once men in power got wind of the formula, they preferred to restrain distribution and keep it and its magical properties to themselves. It’s a powerplay. Were an elixir of youth ever to be developed, you can imagine the titanic struggle to retain and monetise it, not to forget the bureaucratic urge to regulate it.

(3) Adaptation through generations

Evolutionary biology teaches us that species learn to adapt over time. If we were all to become immortal, would we not lose our desire — much less need — to adapt? I mean, have we reached such a level that we are designed for all future life? I seriously doubt it.

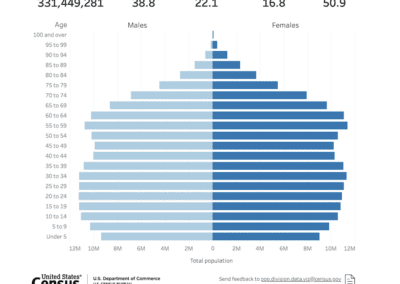

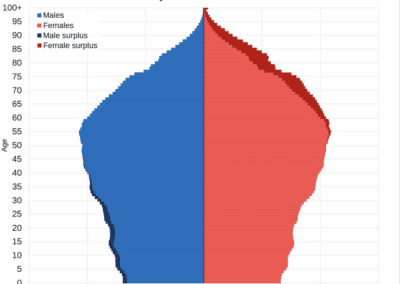

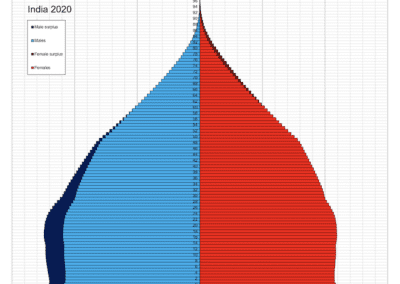

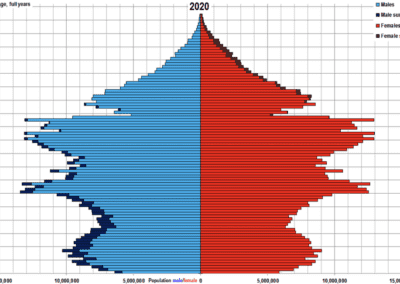

(4) Adaptation of the economy, health care, government…

If we all stopped aging and/or dying, imagine the sea-change effect on our society. Depending on what age that “gift” happens, we’d be stuck in time, so to speak. Given the pyramid of ages today in most western countries where the older population (over 65 years old) is at historic levels and well above the world average of 10%, we’d have a titanic struggle to manage the needs of multi-centenarians. In the USA, the proportion of the population over 65 is presently at 17%, while it sits on average at 21% for the 27 members of the EU. Meanwhile, China is presently at 14% and India at 7%. Imagine what would happen just for a second if the world’s population stopped aging. How would state-run programs be funded? How would the health care systems have to change? In this fairy land, do we get to do away with all health issues, therefore with no need for doctors and hospitals? Would some populations be allowed to continue reproducing while others would be blocked? It would, to understate the case, cause a seismic revolution.

(5) Excitement. Boredom. Deadlines.

If the prior arguments haven’t won your favour, I posit that a life of immortality will be eerily unfulfilling. Imagine a life (or work) without deadlines? How much would we ever get done? As I like to say, an adventure without risk is not an adventure; and a life without adventure, is a life less complete. Although, I’m mightily tempted to go further and say that a life without adventure isn’t a life. A life that doesn’t have an end or include risk seems utterly boring. As it is, many people are bored with their current existence. There’s a thrill in risking things, including your own safety. Think of skiing. It doesn’t have to be life-threatening, but every skier or snowboarder knows that these activities entail dangers, and yet they continue to seek the thrill (until, like me, you end up with too many ACL injuries!)

At the end of the day, life is in function of death. Without death, there would be no life.

Our generation deserves it?

I don’t know anyone who doesn’t look at the passing of time without a bit of curiosity, if not doubt and fear. It doesn’t need a new year’s celebration to put ending of life on Earth on the agenda. After all, death is about as scary as it gets (other than public speaking, some speculate). Aging and death have accompanied life from the beginning of time. It is what characterises our life: that we are finite in body. Then, on what basis, I ask, does ‘our’ generation deserve to have everlasting life? We have an epidemic of loneliness in many western countries, and record levels of anxiety and depression, not to forget suicide rates, in the US (per the WSJ). If you were to scan the headlines over the last few years, the world seems not to be a safer, better place. What makes this current world population — or at least its figureheads, billionaires and celebrities — merit a painfree, ageless life?

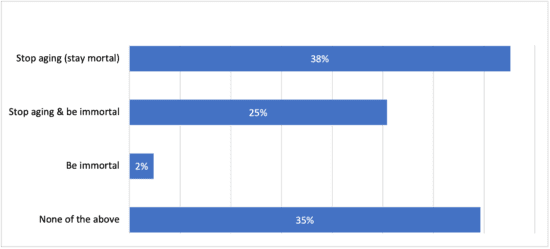

The individuals that are scrambling to prolong their lives and/or defy death all seem to share an an outsized ego. I’m sure you will have noticed — or read about — a seeming rise in narcissism? As explained in this HBR article, “[n]arcissism (diagnosed or undiagnosed) is a personality trait characterised by high levels of entitlement, delusional and inflated self-views, and a general disregard for the interests, feelings, and wellbeing of others.” While the existence of a narcissistic epidemic is hotly debated, this HBR article documents research by psychologist, Jean Twenge, using a clinical measure of narcissism, that shows that “narcissism increased by 30% in the U.S. between the late 1970s and the mid 2000s.” And I think it’s safe to say that levels of entitlement and self-aggrandisement haven’t decreased in the past twenty years. If anything, the trend seems to continue inexorably higher, in proportion to the presence of social media, the increase of families with two or less kids, the lack of community, and a decline in a sense of service. With so many people showing signs of narcissism (i.e. not necessarily diagnosed with a Narcissistic disorder), the hubris is palpable. It would not be surprising to read that many people would be in favour of living longer or forever. To that end, I put out a poll at the very end of 2023, to see what people would say. I posted it on both X/Twitter and LinkedIn, where I asked the following question:

If you had the possibility today, which would you choose?

- Stop aging (stay mortal)

- Be immortal

- Stop aging and be immortal

- None of the above

The answer from 122 respondents, shows that, like Odysseus, a little over 1/3 (35%) are not in favour of this anti-aging, immortality kick (none of the above). Meanwhile, 38% said that they would seek to stop aging, while staying mortal. One quarter would like to stop aging and be immortal. If a total of 27% are in favour of their own immortality, it stands to reason that nearly 3 out of 4 are ok with their mortality.

But the truly galling point here is to believe that in the history of humanity, any of us believes that our generation deserves to live forever? The very thought of it seems improperly selfish and totally deluded.

A lack of mattering

How does one have coherence and meaning in our terrestrial (merely mortal) life, when what we are vying for, spending our dollars and (ironically not un-) limited time, is to have eternal life? Clearly, if the project of postponing or eradicating death doesn’t happen, it will create a whole other level of an existential crisis. In a world where many people are suffering from a crisis of meaning, this chase for the golden elixir is not only elusive, it’s destructive. To use the term of John Vervaeke, the Canadian psychologist, this is the antithesis of “mattering.” Vervaeke described mattering in his podcast on Unherd, as “the sense of being connected to something beyond yourself that has a reality and a value independent of your ego-centric preferences.” Vervaeke suggests that, to find your own meaning (or mattering), you need to be able to answer at least one, but preferably both of these questions:

- What do you want to exist, even if you don’t?

- How much of a difference do you make to it [i.e. your intention or purpose] now?

In the case of anti-aging and death-defying potions, the intention of the billionaires is singularly egocentric, and is lacking in reality. Not only is this ‘hope’ a case of wild hubris, it smacks of artifice. With Silicon Valley in the San Francisco area casting its venture capital and vast angelic investments into the science of immortality, down south 380 miles, Hollywood is turning out films that pander to our fears and wildest dreams around artificial intelligence. Films such as “Her” (2013), “Ex Machina” (2014), “Zelos” (a Dutch film made in 2015), “Zoe” (2018) and the 2001 Steven Spielberg film, “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” (featuring William Hurt, Frances O’Connor and Jude Law) worry about the humanisation of machines and AI. Forgetting the phantasmagorical and generally absurd aspects of this latter Spielberg film, it does bring up a number of legitimate existential questions and issues, as when the AI kid, David, implores his mortal mother, Monica, “I hope you never die.” The film ‘twist’ is that the “real” son, Martin, who suffered a critical but not fatal accident, essentially comes back from the dead and is augmented by mechanical legs. Throughout the film, the line between machine and human is indelibly blurred. What is the difference between an immortal kid and an infinite robot in the anthropomorphic form of a child?

The big issue with adults seeking immortality is that it sends the entirely wrong message to the world, and to our kids. It rejects the idea that we are finite. What worse lie than to suggest to children that you’ll live forever. If there is one big old pink elephant in the room, in the way society is developing, it is that we are encouraging our children to believe only in convenience and efficiency, to seek a painless and risk-free existence, and ideally to strive for immortality. I’ve been stunned to talk to young men in their late 20s, early 30s, who have latched on to the immortality thread. They are excited at the prospect of (a) making money and (b) possibly living a lot longer. And yet, they have never produced anything. They typically don’t even have a family yet… The belief that these young men deserve to live forever strikes me as quite preposterous. Moreover, I feel they are in for a chronic, if not catastrophic disappointment of a life.

In Spielberg’s film, “Artificial Intelligence,” mentioned above, the mother Monica presciently says to her “mecha” son, David, “I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about the world.” In other words, she didn’t prepare her child for the realities of life. I would add that society in the west, today, is ill-preparing its offspring to deal with the harsher realities of the world. If media is constantly fanning the flames of fear, the rest of society (read: politically correct zealotry, virtue-signalling do-gooders and social justice warriors) is propagating a vision of the world that does little to prepare children for the true challenges of life. The biggest frame of all is the assurance of death. Along the way, we should understand that life is about handling challenge, managing pain, hardships, and loss, and coming to grips with our mortality. As the Stoics wisely say, it’s not what happens to you that matters, it’s how you react to and deal with the hiccoughs that makes life fascinating, troublesome and, yet, worthwhile. The best advice I’ve heard is to focus on what matters and on that which you can control. This is the key to a good life.

In Spielberg’s film, “Artificial Intelligence,” mentioned above, the mother Monica presciently says to her “mecha” son, David, “I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about the world.” In other words, she didn’t prepare her child for the realities of life. I would add that society in the west, today, is ill-preparing its offspring to deal with the harsher realities of the world. If media is constantly fanning the flames of fear, the rest of society (read: politically correct zealotry, virtue-signalling do-gooders and social justice warriors) is propagating a vision of the world that does little to prepare children for the true challenges of life. The biggest frame of all is the assurance of death. Along the way, we should understand that life is about handling challenge, managing pain, hardships, and loss, and coming to grips with our mortality. As the Stoics wisely say, it’s not what happens to you that matters, it’s how you react to and deal with the hiccoughs that makes life fascinating, troublesome and, yet, worthwhile. The best advice I’ve heard is to focus on what matters and on that which you can control. This is the key to a good life.