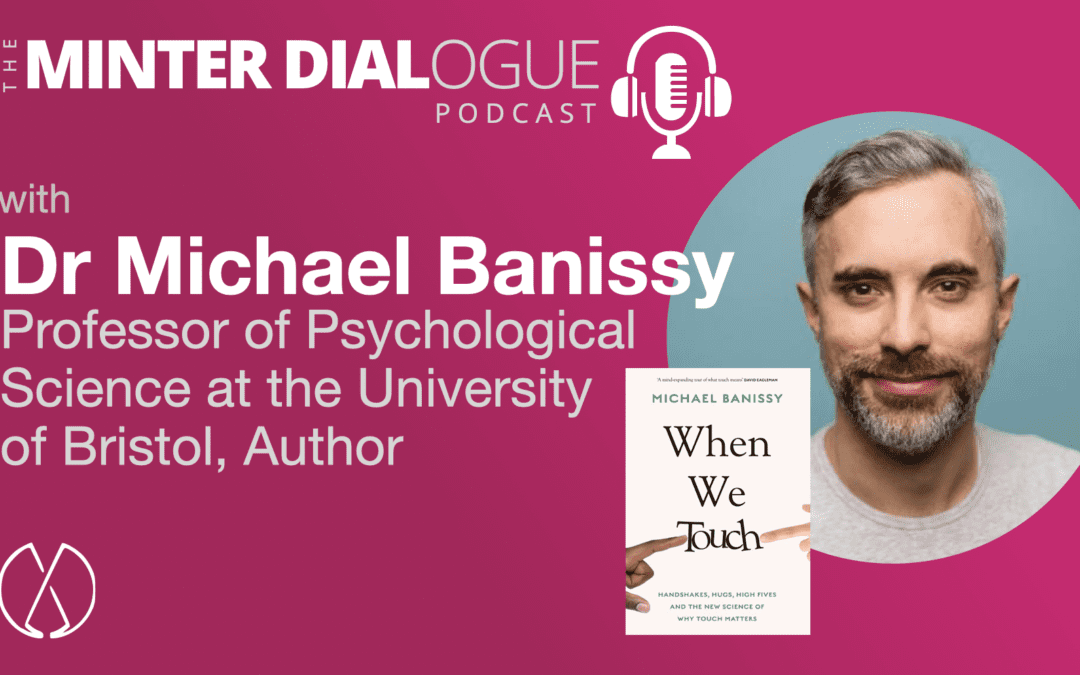

Minter Dialogue with Michael Banissy

Michael Banissy BSc, MSc, PhD is a Professor and Head of Psychological Science at the University of Bristol. An expert in social interactions and relationships, Michael has worked as a social neuroscientist for over ten years. He studies affection, communication, empathy, sleep, and touch. He’s author of a timely book, “When We Touch, Handshakes, Hugs, High Fives and the new science of why touch matters” (Hachette). In this conversation, we discuss his route to becoming an expert of touch, his associated interest in empathy, the role of touch in our upbringing, insights into the effects of the policies of the Covid pandemic, and how we all have different touch profiles and personalities.

Please send me your questions — as an audio file if you’d like — to nminterdial@gmail.com. Otherwise, below, you’ll find the full transcript of the episode (by Otter.ai) and, of course, you are invited to comment. If you liked the podcast, please take a moment to rate it here.

To connect with Michael Banissy:

- You can check out his profile and publications at University of Bristol

- Find/follow Michael on Twitter

- Find/follow Michael Banissy on LinkedIn

Further resources for the Minter Dialogue podcast:

Meanwhile, you can find my other interviews on the Minter Dialogue Show in this podcast tab, on Megaphone or via Apple Podcasts. If you like the show, please go over to rate this podcast via RateThisPodcast!

And for the francophones reading this, if you want to get more podcasts, you can also find my radio show en français over at: MinterDial.fr, on Megaphone or in iTunes.

Music credit: The jingle at the beginning of the show is courtesy of my friend, Pierre Journel, author of the Guitar Channel. And, the new sign-off music is “A Convinced Man,” a song I co-wrote and recorded with Stephanie Singer back in the late 1980s (please excuse the quality of the sound!).

Transcript of full interview of Michael Banissy

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

touch, people, empathy, suppose, tactile, book, pandemic, feel, studies, increasingly, hug, early, sense, experiencing, Michael banissy, years, touchless, sharing, world, interaction

SPEAKERS: Minter Dial, Michael Banissy

Minter Dial

Hello and welcome to Minter Dialogue, episode number 527. My name is Minter Dial, and I’m your host for this podcast, a proud member of the Evergreen Podcast Network. For more information or check out other shows on the network, please go and visit evergreen podcast.com. So, this week’s interview is with Michael Banissy. Michael is a professor and head of Psychological Science at the University of Bristol in the UK. An expert in social interactions and relationships, Michael has worked as a social neuroscientist for over 10 years. He studies affection, communication, empathy, sleep, and touch. He’s also, the author of a timely book, “When we touch, handshakes, hugs high fives the new science of why touch matters.” In this conversation with Michael, we discuss his route to becoming an expert of touch, his associated interests in empathy, the role of touch in our upbringing, insights since the effects of the policies of the COVID pandemic, and how we all have different touch profiles and personalities. A fascinating discussion, you’ll find all the shownotes as usual on Minterdial.com. And if you have a little moment, please go and consider drop in a rating and review. And don’t forget, subscribe to catch all the future episodes. Now for the show. Professor Michael Banissy! There are So, many people I’ve been mentioning you to. I kind of feel I got to know you a little bit. In any event, I devoured your book “When We Touch, handshakes, hugs high fives and the new science of why touch matters” published by Hachette. And we’re gonna get into the US edition. But in your own words, Michael, who are you?

Michael Banissy

Well, firstly, thanks for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here. So, I’m Michael Banissy. I suppose professionally, I’m a psychologist on the head of Psychology at the University of Bristol. But I suppose what took me into that route is I’m very much a people watcher. I’ve been fascinated by people my whole lives, the relationships we have with each other, how we form them, how we build them, how we maintain them. And, you know, a big part of that is touch. And that’s very much been at the heart of my my research for several years now. One well over a decade. And yeah, it all kind of comes back to that whole big question for me of how is it that you know, people we’re kind of we’re messy as people, right? We all have all these things we bring to our allies? How do we come together and build and maintain social relationships? And what plays a role in that? And when can it be positive? When can it be negative? That’s what my work is all about really?

Minter Dial

Well, when you say you’re a psychologist, and you observe people, I’m thinking that’s more like a sociologist.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, true. So, my background is in social neuroscience. So, I always historically studied the brain basis of social interaction. So, how, what happens in our brain when we interact with others? So, I did a lot of mean, all the other Yeah, going on exactly all of those kinds of components. And so, I do lab-based work. But I also, do things like survey-based work, I do behavioral studies, So, might bring people into the lab and measure things like their empathy and how empathic they are towards one another, which, of course, is a really hard thing to do, because how do you measure empathy? But that’s probably a different topic.

Minter Dial

And it has me interested, dead on!

Michael Banissy

And we do more observational work. So, you know, we’ve done studies where we’ve just been out watching how people interact, you know, on campus, you know, to people, whether they hug each other, whether they don’t hug each other those types of interactions. So, we were very much a mixed methods approach. You might in my lab, it’s this blend of neuroscience psychology to a degree, some sociology as well in there. I kind of think often the key is, what’s the question? And then you think about how best to answer that question. I don’t think there’s ever one perfect method, right? You want mixed methods that converge together on a common answer, then hopefully, you’re getting to the right answer. But it’s never quite that simple. Of course.

Minter Dial

It seems like it’s a perfect reflection of the messiness of our being.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, exactly. I think that’s, that’s one of the things about studying people is you, you quickly recognize that it’s not it’s not like physics, where things are nice, linear, easy formulas, right? People are hard and messy, and they bring nuance, and they bring variants and, you know, one of the big trends that I’ve really valued over the last, I suppose, yeah, 510 years or so, in psychology is a much greater focus on that nuance. You know, there’s previously there was a lot of work talking about, okay, well, people show this and the kind of the average response and now, recognizing that kind of nuance in between those kinds of fine lines that come between us and play a role from one person to the other.

Minter Dial

In the realm of straight talk, nuance and average doesn’t really sell well. And if you’re publishing papers and trying to get a name and a notoriety, are we have we lost the ability to be black or white?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, it’s tricky, right? Because I mean, I think there’s yeah, there’s headlines obviously grab and headlines obviously, do sell. Right? But I think actually recognizing, I suppose the diversity around the headline, I do think is actually becoming increasingly more well understood and well recognized. I think, increasingly, we are trying to see more spaces where we can get our differences and our perspectives out there, whether people always agree with one another, and people may well fall into camps on that. But I do think that is now recognized as a pretty good approach to try to if you don’t share and understand those differences, those differences begin to grow. Right. So, it’s about how can we, how can we create those spaces? And, you know, the good, good thing and researchers, I think people are getting that across. And I think people are beginning to share that more broadly as well.

Minter Dial

I want to get into your book afterwards. But just another question with regard to your work. To what? So, I’m imagining your teaching classes. Is that still something you do?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, yeah. So, I do I do some teaching. So, in Bristol, I’m the head of psychology. So, I effectively, I kind of oversee all of operations. It’s a kind of, I suppose in the business world, it’s a bit like acting like a mini-CEO. Some people say, you know, because you’ve got the dean. Yeah, you’ve got a good kind of 110 FTE staff. And you’ve got obviously about 1000 students coming through your doors. So, it’s a whole range of people and dynamics to think about. But I do the teaching as well. So, I teach around things like social neuroscience and social interaction. That’s mainly where I do my work. I supervise students, we run experimental projects together, and I kind of supervise their work. And that’s from all levels. Right, that’s undergraduate, right the way through to PhD. And then I have staff that work with me as researchers in my lab in my team. So, it’s a very, very role effectively.

Minter Dial

And my question that I wanted to ask about your teaching was, to what extent teaching has changed over the years for you?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, I mean, it’s, I think, it’s always changing. To be fair, I think it’s, I think, increasingly, there’s been changes in, in methods, I guess, when I was coming through the system was very much a kind of chalk and talk style, you know, people would stand up if the lecture I remember actually being an electron, where I think a professor literally read from a book to me, and I was, I was quite disappointed about that. I was like, well, I could read this at home. You know, so. So, it is that increase on much more interactive components, but small group, large group getting those blends, and I think, an increasing recognition over the years about how we can make teaching, I suppose more inclusive, as well and more accessible, because, you know, that can come from a variety of different ways to assess students, you know, I mean, historically, teaching has been sometimes about the kind of one big exam at the end of the year kind of thing, which obviously plays to some people’s strengths. But more and more now, it’s kind of blending with, you know, multiple assessments, different types of assessments, maybe doing a podcast, rather than writing an essay, all of these different kinds of things. So, there’s getting a much more diversity in it. And an understanding, and I guess, now as we move forward a big thing for us that we’re now very much thinking about in teaching, as, of course, the rise of AI, which I know is another topic that will probably pique your interest. But of course, how do you how do you how do you engage with teaching or assessment with AI in the world? And So, it’s continually moving? And I think that’s quite exciting.

Minter Dial

Yeah, it’s actually a bit hidden, like my sub plot, or a sub question really is around the place for debate, a lively conversation. So, if I flashback to my generation, we would have frolicking very lively debate now where it felt like it was free roam. What I am gaining or garnering from reports and media, is it doesn’t seem to be quite as lively the debate. It’s more tempered, maybe more nuanced. But one could also, say it’s more closed.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, it’s interesting to think about it that way. I mean, I think it also, depends on where in the world you’re looking at, as well. Right. So, I think a lot of those headlines about very kind of closed debate, often people connect to some of the things particularly in North America and some of those kind of areas there. I mean, I think my experience of it on the ground is I think there is there’s very still very much open debate. I mean, I think it’s in the UK at least I think it’s it’s there. I think it’s about ensuring that those debates are, I suppose, structured in such a way that everybody involved can feel comfortable to be heard and to be listened and get their voices across and perspectives that are respectful to one another. Right. And I think it’s about how you set those those kinds of boundaries in that space about respectfully listening and disagree. And what that what that means that, of course, there’s a fine line in that, because if something quickly moves to being offensive or problematic, then how are we going to be very cautious, you know, to, to prevent that. But I think a lot of that can often be set by setting the parameters of conversation, and almost, it’s not So, much the rules of engagement, but it’s about just getting the right culture and ethos around that, but I certainly I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t say that. There is no debate in the education setting, I think debate is there. It’s still an active part. It’s just Yeah, I suppose you never know what what it was when you weren’t there? I suppose. So, I can’t I can’t make those comparisons to that time. But I do recognize increasingly there is a concern about Yeah, is is the bait getting, I suppose temper down and watered down? And I think, yes, certainly, from what I’ve seen, not necessarily so. But that’s not to say, you know, that is the case. I mean, I’ve worked to some very lively places, I was at Goldsmiths in the University of London, before moving across. And Goldsmiths is known for being very much a kind of, I suppose, free speech and the climate of challenge and, you know, different views and perspectives. And, and I think certainly, there was a lot of lively debate and activity there as well when I was there. And I see that now, Bristol, as well. So

Minter Dial

I’m glad to hear Alexandra, my daughter who attended Bristol that I know that she’s a fiery, passionate individual, and surely had plenty of good conversations. I think one of the advantages of my schooling in Britain was that I learned to think on my feet and argue. But I also, played rugby. So, I was able to back myself up with some sort of physical, physical presence. I think that also, helps sometimes when you’re being thrust into a lively debate. Sure, can be it’s not physical fights, but physical in terms of mental acuity.

Michael Banissy

I think that ability to kind of think on your feet and respond. And yeah, that kind of strength of mind in it as well. Right?

Minter Dial

Right! So, we just mentioned North America, and how a little bit different it is, you wrote the book When We Touch for Hachette for the European version. And to my great surprise, the title was quite different, as the title in US, published by Chronicle Prism, was, instead of “When we touch handshakes, hugs, high fives”, and so it was “Touch Matters, handshakes, hugs, and the new science on how touch can enhance your well-being.” Okay, So, tell us about that change how you were not involved in it. And how much of the text had to be changed? Other than just, -our to just -or?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, So, So, yeah. So, the story of the book was very much started off with the UK version, that was the version that we sold the rights to, to begin with. And when we touch was always the original title. That was the title from book proposal, right the way through to the publication. And, yeah, partway through the process. It was just after it was quite early on, just after the first draft was submitted, we brought the US publisher, you know, they came on board. And I think in the process, they were like, well, actually, you know, starting to read this, we kind of think actually, the more directness of the title, touch matters for them, they thought that their audiences, their marketing, may well just connect better with that, more So, than when we touch I think, the reason for when we touch as you know, the book has got a lot about human contact, right, human touch. So, we wanted to get that when we touch that kind of we’re coming together. But on the flip side of that, I suppose there is a broad message throughout the whole book, right about the fact that touch is actually a really important part of our lives. And, you know, So, I think, going more direct with touch matters does get that out there. And that’s part of the messaging. And, of course, I was, it was checked with me, would I feel comfortable with the change in title? How did I feel about it? And I was quite happy with it. I was I was open to the idea of having it. I mean, I think, yeah, for me, there’s also, an interesting part in that because there’s touch matters in terms of the directness. But of course, the book is all about, I suppose the different matters of touch. And you could interpret it in that way. So, I quite I quite liked the title as well in that context.

Minter Dial

What about the content itself, whether there are any major edits that were involved?

Michael Banissy

Largely the content is very similar between the two, the two books, actually. And I think that was also, partly because, you know, throughout the editorial process, we have both the UK and the US editor working at the same time as we were developing it. So, you know, it’s very interesting to kind of get the different feedback of what each I suppose audience and market might be interested in. And I think we tried to strike that balance as we were, as we were going through making sure you know, kind of balance of take-home messages and how you can maybe apply things in your life and things like this, which certainly was a key focus for the North American market, that was a key part to that. Tree, Ricky keen to bring in So, So, it kind of came in, throughout the development of the book rather than the final version? Because we’re people we’re in So, early, you know, I think if, if it was one of those things where the book had been published in the UK, and then there was lead time before the US version, maybe more things might have changed, but actually, because both publishers are onboard quite early on in the process. So, shortly after the first main draft actually meant that we started to work that way. Obviously, work for me work for me as an author to make the edits and you know, even a small change, as I’m sure you all know, right? Even a small change in one chapter has a knock-on effect somewhere else. So, it’s quite, it’s quite a time consuming process to make all those different dynamics. But um, yeah, in my case, it worked well, having both the UK and the US editor because it also, gave me a diversity of perspective on it, right, which was useful, actually, just to think about, oh, I hadn’t thought about it that way. Or, you know, yeah, certainly, some of the components where you’re, you’re talking about one element and might get changed, because maybe it won’t quite work. So, well. That’d be like, in one of the chapters, we talk a bit about workplace touch. And actually, I recall, in some of the early drafts, I was tying in some of the work around politics at the time, and particularly in the US, because there’d been a lot of conversations about, obviously, Trump and Biden and these kinds of dynamics, which, in the end, we opted to go about it in a very different way, because, you know, probably wasn’t adding sufficient value to the book to have that debate in there. And of course, it’s quite a polarizing debate, I suppose if you’re a Democrat or a Republican, So, there’s, there’s balances to be struck that you sometimes have to do as you go.

Minter Dial

Well, the concept of politics of touch is, is something that I ran into for sure. But probably not in in a sort of Democratic / Republican kind of way, more in, in a general human politics, maybe small p, in the way, what it reveals in the messaging that we’re doing through the touch. So, I came at it from this. So, let’s start. I mean, we’re not starting, but at this point, tell us, Michael, about your journey into touch. Because, obviously, things like me, too, and the pandemic brought touch to the fore. But you’ve been studying and I’d love you, as you describe in the book, the how, why touch?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, I mean, it’s been it’s been an interesting journey, because I suppose I link it back to that fact. I’m interested in how people interact, how they form, mate bonds, make relationships through their lives, how do they how do they lost and how to how do we maintain them. And one of the things that I found, to a degree frustrating when I first started out in psychology I was reading lots of research so much on vision, as the sense to our emotions, to our ability to socially interact, which makes perfect sense. We rely on it all the time. But there was a real lack of research around some of the other senses and particularly touch and for me, I was like, well, that’s really surprising, because touch is one of the first senses that we develop, you know, we, we, you know, responding often to touch even in the third trimester, right, during pregnancy, there’s evidence that the baby’s will, well, kind of fetuses will respond, you know, to with tactile exploration. So, it’s there really early on. And you know, certainly from the first moments of our lives, we can often use touch to build those bonds with our caregivers, right are really important, but it’s, it’s also, there right away until the end of life, I mean, effective touch and this is something that in science we refer to as those kinds of I suppose, emotionally supportive touches, you know, those kinds of comforting touches, our sensitivity to that is present, right the way through until our late 90s. You know, we could go for longer, it’s just that’s only how far the data’s gone to you, right? So, from the first moment, that life right the way through to the end touches with us, it’s a really important part of our social relationships. But what I was somewhat disappointed in very early on was, where’s the research on it? And it was somewhat missing. It was a missing piece. And in a strange way, actually, despite that frustration, I didn’t start off studying touch I started off start empathy, funnily enough, and, and, and one of the interesting things about empathy that when I was working on it was that we were studying the brain systems that are involved in empathy. And we kept seeing a certain set of brain regions that were becoming active when, when people were observing other people experiencing sensations, right and experiencing states. And often they involved the somatosensory system or somatosensory related cortices. And these are parts of the brain that are involved in experiencing touch. So, there was something about sharing someone else’s state, and these tactile systems that were playing a role. And So, these tactile systems, part of the reason people think they become involved in in empathy is because they think, Well, when you see someone feeling a state, you almost kind of imagine what it might be like to feel that state yourself. Right, you might map it on to your own experiences, those own tactile experiences, to kind of long story short, because I’m not here to talk about empathy, right? But, that brought the somatosensory system and touch back into my research, which made me dig more into it. And, and in that sense, I started to dig deeper and deeper and start just to look at touch on its own as a sense, how does it work? How do we use it to share interactions with one another. And this then led to again, big projects, you know, ranging from studies in the lab to a big project with the BBC that we ran around, blocked down around 2020. Not knowing lockdown was coming, of course, was a big deal. Yeah, exactly. Just to kind of explore what touch means in the world today. And, you know, how important is it to things like our health and our well-being, and so forth.

Minter Dial

Certainly, I want to get into that just observation, you said, you know that there’s a lot about the eyes with relationship. But I mean, I have to imagine there’s also, a lot about hearing the tone of voice. My wife constantly talks about the sense of smell, and how those fare gnomes are vital as for her.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think I think it’s, it’s also, very easy in our conversation. Now, we keep talking about touch, right? Or what’s the nature of the nature of the conversation, but, but I think we’ve all the senses, we have to keep in mind that the world we experience around us isn’t just a single cent, right? It’s a combination, a lot of the time of those senses and So, someone’s smell can impact how you respond to their touch, you know? You know, it can impact Yeah, you know, the same what you hear could impact based on what you see, right, there’s all these dynamics where our senses are interacting, we experience them as one unitary whole, it just happens that in science, we tend to study them more and more in isolation. But that kind of multi-sensory world is vital to our world in general. And, of course, our social webs.

Minter Dial

So, my gut, says, Michael Banissy, is going through his early days. And all of a sudden, he discovers that there’s no bloody science of touch, really, there’s not enough data. Oh, this is a goldmine. I’m thinking, at some level, it has to be exciting to be discovered.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, it doesn’t mean it’s when you when you don’t land on something that is near and you can do that work. It’s incredibly exciting, because you’re at the forefront of doing research on it. Right? And actually, you know, and you get to start working with very interesting people, you know, around the world collaborating on it, but as you’re pioneering, yeah, and also, and also, people who do you work with in research, because one of the key parts of my research is that we’ve often worked with people have very unusual experiences. So, people that might just experience the world very differently just for a subtle change in how their brains developed. And one group, you know, that we’ve worked with very early on were people who feel touch on their own body when they see touch to other people. So, they’re going back to this idea of empathy and touch, right? These people literally are sharing the sensations of other people, and working with those people and pioneering that and learning from them was a fascinating thing. Because if moments of that, you know, things that nobody else in the world knows, right, you’ve got those first snippets. You know, and of course, you’ve got to then go for the very boring academic process of publishing and getting all that out there. And, you know, sometimes that’s, that’s the less fun part. And the fumbling can be a discovery. Right.

Minter Dial

But it can also, be exciting because you are pioneering you’re pushing an area publicly.

Michael Banissy

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. And I think I think once you’ve Yeah, I mean, I think it’s the dynamics of So, for context, academic publishing, going through the peer review process. It’s quite a slow process, but I think once you get out too slow, yeah, exactly. But once you get out there, and then you can go and share it with everybody with the public with others. And that’s brilliant because then you start getting questions right, you start getting questions You haven’t thought about before and might have been my favorite audiences to speak to most of them. It’s not it’s not academic crowd, you know, it is. It’s the public. It’s it’s people who I don’t normally get to speak to in my days of work because they asked me such clever questions that I don’t often get through people who may be thinking that same kind of scientific way that I do, which, of course, good questions do come from that as well. I don’t want to knock my academic community but actually the questions that can come from people who are looking at it, sometimes for the first time, sometimes we’ve a very different lens, it just opens your mind to different possibilities with it. And that that process is brilliant, and certainly one that’s, that’s what keeps you going in research, really.

Minter Dial

I have to imagine that some of those questions come from the mouths of the seven-year-older.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, yeah. Yeah, you do get that you do get that? I mean, I Yeah, one of the things I’ve done lots of, I suppose, public engagement with science throughout my career, and very early on, I was doing events and schools and doing these kinds of things. Were a Brain Awareness Week you go in, and you get some great questions from these from these from these kids, you know, things that do just make you think, wow, okay. And I thought about it that way. But let’s that’s a, that’s a very honest take on that. Let’s think about!

Minter Dial

Unfiltered! So, you had talked about empathy before, and certainly, obviously an area of interest for me you are, I would say, it seems more focused on cognitive psychology. But you have, obviously the exploration of many different types of science in the sense in empathy, there’s various schools that describe empathy. And say, for me, I tend to categorize two types of empathy. One being cognitive, and then the other one, affective. The funny other way of saying it, when you can say emotional empathy, but you could also, say feeling empathy. And this is where there’s like a crossover, and I’ve never thought of it, but touchy empathy, or feeling as in touch, empathy. Tell us? What, if anything is happening on that space? Because it’s really not something I know much about?

Michael Banissy

Yeah. Well, I mean, I think that that idea of that kind of affective empathy, that emotional empathy when you start looking neurologically about, you know, what happens when somebody that an NSC, some see somebody in pain, right, you know, and that says, how are they sharing that experience? Quite often, you will see people recruit similar parts of the brain as when they this is the mirror neuron system all sorts of Yeah, I mean, I mean, says, yeah, So, I mean, you see it for pain, you see it for touch, people tend to just kind of CO represent, right, they tend to activate similar parts of their brain as when they experienced that state themselves. And So, some people do draw those comparisons and kind of say, well, there is that kind of feeling aspect of empathy coming in. So, I think that that can play out in that context. And certainly, we’ve worked with people who do literally say, they feel a physical sensation of touch, or a physical sensation of pain, when they see somebody else experiencing it. So, then if somebody, if they saw somebody being slapped on the face, they would say, they literally physically feel the sensation on their own face. And we’ve been able to show these people, behaviorally, we’ll defer to people that don’t experience in this So, we can kind of verify them reports. We’ve also, shown it neurologically, So, they show different brain responses, or they just tend to appear to be sharing the sensations and, and those people then tend to show heightened affective empathy. So, if you measure their affective empathy on tasks, you know, whether they’re questionnaires or whether they’re computer-based tasks, where we might know what the person was feeling, and you’re trying to see how much do they share it, you tend to see these people show heightened responses that are more sensitive at detecting those types of cues. So, there’s a relationship to a degree between some of this, I suppose, what we might call somatosensory or tactile systems and our empathic responses. Exactly what that relationship is, is one that is very hard to disentangle. You know, and I think that’s one that people argue quite a lot about in the scientific sphere.

Minter Dial

And so, certainly not to be politically correct, but it does make me think about pornography. You’re watching someone else have sex or watching, you know, triple X? Is that what’s happening? I mean, is, are we talking about that sort of empathic feeling? I mean, is that a way of explaining that?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, well, that’s the thing. So, I mean, this is and this comes back to the question of, is it empathy? Is it vicariously sharing? Is that the same as empathy? You know, this goes back to the question, I think of what is empathy, right? Is empathy, the capacity to share the states of somebody else, or is it or other components to it? Like you’ve alluded to, like the cognitive thinking about what somebody might feel in a situation, or maybe it’s about, you know, not just sharing what we think the person is experiencing, but sharing what they’re actually experiencing. Where does that? Where does that break down? Right? Because

Minter Dial

that’s the difference in cognitive and affective. One is the feeling the feelings, no one is thinking I understand.

Michael Banissy

Exactly right. And so, there’s all these dynamics, which of course, tie us back to this really thorny issue of what is empathy to begin with.,

Minter Dial

Better a thorny issue than a horny issue. You mentioned earlier, the idea of being in the womb and the touch that happens there. To what extent to the science show the amount of touch and the type of touch you have as a child, preconditions your later life and your experience of touches, you go for it?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, I mean, it’s, it’s been, it’s very much a really important part of our development. So, there are studies that have looked sad studies really that children who, sadly, are isolated during development, and they didn’t just like touch, I should qualify this, it’s they lacked a general kind of social interaction. And people are looked at how does that impact things like their cognitive development? How does it impact their social relationships, and you can see these negative impacts from not having, you know, from really being touched, deprived early on in life, you also, see that in some of our nonhuman primate relatives, So, people have done work in monkeys, for instance, where you see that if you separate, you know, monkeys from their mothers very early on, and you don’t give them tactile interaction. They don’t have that comforting touch, this can lead to all sorts of altered social behaviors, difficulties forming relationships, maintaining relationships, as they as they age. There’s another line of work as well, which is also, looked at, not necessarily touch deprivation, but just simply look slightly more, let’s say you have a newborn human infant. And you’ve, you have situations where, you know, maybe, for instance, sadly, they can’t have tactile interaction early on. But they can have some but less than another, and people have been tracked, how much does that touch in early life linked to later social skills. And there was a study that came out was only a couple of years ago now, which basically, this study looked at. babies that were born kind of normal term, and had what they might call kind of typical tactile interaction with the caregiver, babies that were born preterm. So, prematurely, and we’re had some tactile interaction, but not much. And in babies that were born preterm, I had no tactile interaction. They, they tracked these kids for 20 years. And they look to how much throughout those years how much social synchrony, So, how in sync they were when interacting with their caregivers. And they found that those that were touched very early on, had more synchronous social interaction. And what they then went on to show was that even 20 years later, So, when they were adults, if you put those kids, you know, now adults, and you showed them, somebody else experiencing an emotional state, and you looked at brain networks involved in empathy, you found those that had more touch, and were more socially in sync with their parents, as they aged, they showed more empathy towards others. So, those very early moments of touch, even 20 years later, some kind of level of linkage being connected between them. So, touch is really important, from very early on.

Minter Dial

And I really enjoyed the passages in your book about the pre meeting in the primates, how they observed, oh, yeah, what was going on in that it’s always been something fascinating. But I want to get into before we close on, on what’s happened over the last few years with the pandemic and such, but there’s another area which is of interest to me, which is the touched and the touchy one touching, and to what extent touching is as or not useful, if you will, in in stimulating the brain and the feelings?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, I mean, I mean, touch is an incredibly powerful social cue. And so, I don’t know, there’s not necessarily a particular study that says right, if you touch this amount, you’ll see this much brain activity. We don’t we don’t quite have that side of data. To answer the question specifically, but, but what we do know is that for some of us, in some social situations, touch is actually our preferred nonverbal cue. So, to express an emotion like sympathy, or to express an emotion like compassion and love, often, historically, people opt to use touches that as that as the method to convey that right Of course, there’s context that matters in that, that’s just if you’re giving people free choice, right? Where they feel quite comfortable, what will they use? You know, one could imagine that maybe if you’re in an environment that you don’t feel comfortable in touching, some people might say, the workplace, for example, then that person may not want to express sympathy for touching, right? So, So, there’s dynamics to that. But certainly touch is a really powerful cue. And, you know, it can have very subtle effects as well, that we don’t always realize, and I talked about this a bit earlier in the book, right. So, for instance, somebody simply placing an arm on your shoulder, when they make a request to you, you can be more likely to comply with the request. So, there’s studies in, in bus drivers, for instance, sharing this was in France, back in the 90s, I think, or early 2000s. And so, they had people got on a bus, and they didn’t have enough money to pay for the ride. And so, at that moment, either they touched a bus driver when they made the request, or they didn’t. And that simple act of touching the bus driver, that addition led to bus drivers being more likely to let them get on and have the free ride. And you know, that’s just one example. There’s, there’s many of these scattered from the 1970s, right the way through to even a year ago, there were studies coming out showing that even if someone touches you on the arm, when you’re giving the giving you the bill, you might be more likely to give them a bigger tip or spend more money in their shop or something like this. There’s a whole range of examples where punches a really powerful, subtle social cue, as well as the more expressive, I suppose explicit cues, we might see like someone giving us a hug or something like that, right.

Minter Dial

Yeah, it was making me think of when you’re lost for words, where you just in the silence, that the touch speaks the volume?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, it does. So, I mean, sometimes words just won’t quite get the message across. Right. But as simple comforting touch can do that. Right. You know, if you’ve, you know, I think, particularly for a lot of people, I think they will think about that in situations of support and care, right in those in those moments where it’s a difficult scenario. Maybe you don’t have the words, but there’s something about touch that can ground us and connect us to one another and, and help to kind of get that message of, I suppose, calmness and came across.

Minter Dial

So, I’d be remiss if I don’t bring up this specific family issue. In the dial household, which, where we I’ve been identified as someone who tends to touch too much. When it comes to dinners, and my dinner partners beside me, I will touch them, as I’m talking I’m very sort of touchy feely as it comes to that. At the same time, I’m called out for not being very bisous, which means not often giving kisses and cuddly. Is that a condition?

Michael Banissy

Like? No, no, no, that I’m aware of? I think I think you probably reflect on the fact that we all have, we all have different touch personas, right? We’re all we have different levels of tactility. And, and even that’s not not the easiest way to define it. Because, you know, you might have someone who touches a lot in the house but won’t touch a lot outside of the house, right? There’s all there’s nuances, because touches is not just about what we maybe naturally have as our tendencies, it is influenced by our context, but all these different things. And then you have different types of touch behaviors, right? You can have somebody who will describe themselves is incredibly tactile, you know, a really tactile person, but, you know, they might just hate it if someone I don’t know gives them hardcore strokes. They are more something like that another person I said. Well, that’s my favorite tactile experience, you know, touch. It is a sense that it unites us, but it also, divides us right, both in opinions and in other ways as well.

Minter Dial

In this particular case, massage is the counter point. To be touchy feely, but don’t like massage? Yeah. So, interesting. Let’s focus on the last part of our chat about what’s happened over the last few years. Obviously, you did that study right before locked down. My observation, Michael, and this is certain sort of non-scientific, hopefully somewhat sociological at some level. The observation I have is that the impact of the pandemic was a heightening of our sanitisation or us making things clean and social distancing. wearing masks and gloves. E commerce is great. So, we don’t have to go to a shop. Pay with the phones. We don’t have to touch cash, the dirtiness it feels like we’ve had a kind of a titanic move away from touch. And what are your readings on that? And how is that good? And what should we do about it?

Michael Banissy

Yeah, I mean, I think it’s, I found the pandemics somewhat paradoxical in a way. And the reason for that is I think I think to a degree, you’re right, I think it has heightened and move to a slightly more touchless society. And I think I think that certainly has played out in all sorts of examples, right, we’re seeing more and more like touchless. touchscreens, and even things like this now coming out. Right. And, and that was a trend that was there before the pandemic, but I think often seismic events, speed trends up, actually. So, I think I think increasingly, we’re seeing that play out. But on the flip side, you know, I mean, one of the things that, that we asked people to share in our survey, and, you know, the context, the survey was, we asked about 40,000 people from 112 countries worldwide, you know, in this view, just before the pandemic, not knowing it, but we asked about, do you get enough touching your life, you know, and actually 54% of people, which was the majority said, they did, and only 4% of people said, they got too much. As we went through the pandemic, other research came out showing 80% of people were saying they weren’t getting enough touching their lives. So, there was something paradoxical about it, in that we were going increasingly touchless. But people were saying, I’m not getting enough touch in my life. And I do think there’s a part of the pandemic that has also, brought people out of it, where there’s a new appreciation for those, I suppose, socially supportive components of touch that matter to an individual, and that doesn’t necessarily have to be publicly on the street, right? It might be, I missed that hug from my friend that I used to get right. And now I’m making sure and I appreciate that a bit more now. Or maybe it was because I couldn’t hug my parents, right. And So, I think there’s the subtleties in it insofar as, yes, we probably are going increasingly touch lists in certain scenarios. But I also, think there’s an appreciation now of touch for people who are actually like, well, actually, no, I missed that when it was taken away, you know, I missed the ability to touch a product in a shop and hold it for some people will have been a thing. Right. So, I think that is there. You know, So, there’s different dynamics to it. And but no doubt, there is no doubt I suppose that we are becoming increasingly touchless. In our interactions. I think that is that is a challenge that we do face, I say a challenge, but it’s also, create some opportunities as well. Because if you work in a tech space, how can you? How can you give these people that are missing touch in their life, a sense of touch, right, and, sending the machines, your art, you know, and I think that’s the that is that is increasingly an area of big focus now around, you know, what people call haptic wellness, right? It’s this idea of how you can use technology to provide a sense of touch to people. And that could be saying to someone, but you’ve got a wearable on your body that vibrates, you know, let’s say on your wrist, send you a message. And that could be somebody trying to send you a comforting squeeze of your arm, because they’re not there with you. But you know that I’m sending it to you. So, there’s a meaning behind it. I mean, that’s one example. Some people are doing work now with social robots, right? So, they’re building these companions in Japan a lot. Yeah, exactly. Right. And, or even a cushion that you can hold that might brief with you. Right? That’s something we’ve been developing in Bristol, so. So, there’s all these things that are in our development, just trying to find ways because, you know, not everyone can have touch in their lives. Not everyone has got that person, right. But touch does have a really important impact on people’s health and their well-being. You know, it’s a very common sense to ground a lot of people and, and maybe a hug from someone else isn’t going to do that for someone, maybe they would prefer that sense from to come from something more machine or inanimate, right?

Minter Dial

Well, So, my line of questioning, as I talked about in my book about empathy and AI, is that it’s all very well delegating empathy to the machine. But is that really the right thing to do? Because maybe we have a statement or position as to whether hugging, shaking, hands kissing, smelling each other actually, is the better version of humanity?

Michael Banissy

And a really important part of that is that is we don’t know if those machine types of touch actually will carry the same benefits, right? So, So, there is a lot of evidence now showing, for instance, that having supportive hugs from somebody, like physically supportive hugs from another person, or even hugging yourself can be really beneficial to buffer your responses against stressful situations. If you have these hugs before you get sick and might actually impact how quickly you recover from a virus as well.

Minter Dial

You mentioned that in the book, about how touch is actually salutary. It can help you with your immunity.

Michael Banissy

It can do all these things. And So, So, there’s this evidence on physical contact right in that now, more and more now people are saying, Well, how about if we send somebody a virtual hug? What if someone puts, I don’t know, a vest on that they can feel a hug, send from miles away. And we don’t know. I mean, that’s, we don’t know if that will help in the same way as a physical hardware, right? On the one hand, you could say, well, it shows social support. And we know that showing social support plays a role. But that doesn’t explain all of the ways in which hacking can help our health and our well-being. So, there is something about the physical contact. And, you know, I think there’s, there’s this question of, you know, are we going to is digital touch ever going to fully replace human tactile interaction? I don’t, I don’t immediately think it will. Because I do think there is something special about human physical contact that we, that we crave, and that other animals in the world crave, right? So, ever we see on So, many levels. And, and, you know, touch has been with us for So, long, in So, many ways. You know, even something like a handshake. I mean, you look at how long that’s been around, and people like, well, that might disappear post COVID. It’s back. You know, it’s maybe not as common as it was before. Maybe people get confused with a fist bump, but there still is still something tactile, right connected to it.

Minter Dial

Well, my feeling is positionally that we better, stay messy. Because messy is dirty. Messy is not easy. And not easy. The imperfect the dirt, that actually is, is what we’re about and dealing with that. And if we delegate everything and sanitize everything, I don’t feel like that’s a world really interesting to live in.

Michael Banissy

Yeah, yeah. Where do those kinds of backgrounding and connection to our world and our environment come from? And those opportunities, I think, drive innovation, right? Because I think being connected to yourself, others and the world around you, that’s how we have we’ve created over the years as a species, right? So, how, what if we lose that and that becomes quite concerning, right?

Minter Dial

And there’s plenty of, of material that talks about how technology is accelerating, and pieces that are far beyond our ability as human beings to evolve. And so, maybe the role here is to somehow slow down the evolution or at least put our feet down. Like a dog who doesn’t want to go and stop the leash pulling me towards this in an ineluctable sanitized machine led world.

Michael Banissy

Yeah. Yeah, that’s a beautiful way to put it really.

Minter Dial

It was just an image that came to my mind, Michael, what do you what are you working on? In the future? What is something that give us a view into the future of Michael Banissy? Work?

Michael Banissy

Yes, my work has always been really varied. I should probably say that. So, we are we are continuing our work on touch. We’re doing a lot of work now, actually trying to do some of those comparisons about digital and physical touch, right? When do they help our health and well-being in the same way? Do they carry those components? But alongside that we’re doing work looking at things like sleep now, increasingly. So, we’re looking at how does touch prior to bed, you know, how you know, that’s gonna be a cuddle, that could be, you know, sustained components, how do those impacts sleep? And how does that then play forward? And looking at other areas, as I kind of alluded to, I suppose in a conversation, I mean, we’ve done lots of work over the years on empathy, we’re doing a lot more work now on listening, we’re really becoming quite interested in listening as as a sense that we use and, and very much in that kind of conversational way, you know, and affection more broadly, this is a big part of what we’re interested in, because the work on touch for us has mainly been about sharing affection and affection of touch, but you can share affection in many ways, right? You might write somebody a note, you might send them a message, you could make a smiley, yeah, made them a coffee, no one is smile, right? And the data is now increasingly coming in to show that actually giving affection to someone can almost be as good as receiving affection. Back to the touched and touchy. So, we’re now really becoming quite interested in this as a topic of investigation. And yeah, it’s a whole mixed bag really, as well as some slightly kind of unusual stuff in there. Like, trying to understand experiences like ASMR, which is where you know, people kind of get these kinds of tingles from hearing repetitive things or whispers.

Minter Dial

I just had on my podcast, a man who wrote “How we listen,” by Oscar Trimboli. And obviously, I was also, I miss pronounced the name of your book, “Why we touch” because it made me think of “Why we sleep,” which is also, a great book. Yeah. And so, a couple of times, yeah, I misquoted your book is Why we why we touch? That’s really when we touch handshakes, hugs high fives, the new signs of high touch matters. Michael been a total pleasure listening to you. I feel touched. And how can people follow your work? Get your book, one of the best ways to be in touch with you. I know you have a few good links a good time to plug everything.

Michael Banissy

Yes, yes. I mean, everything’s on my website, which is wwe.fantasy.com, which is an unusual name. So, it’s Banissy. And there’s a page on there specifically about the books and you can go through the landing page there if you want to order the books anywhere. But there’s updates on all the work that we’re doing available on that as well.

Minter Dial

Brilliant, keep up the good work, and hopefully we will get a chance to maybe hug in person, or at least shake your hand as it feels right to do. Thank you So, much, Michael.

Michael Banissy

Pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Minter Dial

Thanks for having listened to this episode of the Minter Dialogue podcast. If you’d like to show we’d like to support me, please consider a donation on patreon.com/minterdial. You can also, subscribe on your favorite podcast service and his ever: rating and reviews are the real currency podcasts. You’ll find the show notes with over 2000 and more blog posts on minterdial.com Check out my documentary film and four books, including my last one “You Lead, How being yourself makes you a better leader.” And to finish here’s a song I wrote Stephanie Singer: A convinced man.

A Convinced Man by Minter Dial & Stephanie Singer

I like the feel of a stranger

Tucked around me

Precipitating the danger

To feel free

Trust is the reason

Still I won’t toe the line.

I sit here passively

Hope for your respect

Anticipating the thrill of your intellect

Maybe I tell myself

There’s no use in me lying.

I’m a convinced man,

Building an urge

A convinced man,

To live and die submerged.

A convinced man,

In the arms of a woman

I’m a convinced man

Challenge my fate

I’m a convinced man

Competition’s innate

A convinced man

In the arms of a woman.

Despise revenges

And struggle to see

Live for the challenge

So life’s not incomplete

What’s wrong with challenge

I know soon we all die

I like the feel of a stranger

Tucked around me

Precipitating the danger

To feel free,

Trust in my reason

And let me show you why.

I’m a convinced man

Practicing my lines

I’m a convinced man

Here in these confines

A convinced man

In the arms of a woman.

I’m a convinced man

Put me to the test

I’m a convinced man

I’m ready for an arrest

I’m a convinced man

In the arms of a woman.

I’m a convinced man… so convinced

You convince me, yeah baby,

I’m a convinced man

In the arms of a woman…

Lyrics by Minter Dial

Arrangement by Stephanie Singer.

Minter Dial

Minter Dial is an international professional speaker, author & consultant on Leadership, Branding and Transformation. After a successful international career at L’Oréal, Minter Dial returned to his entrepreneurial roots and has spent the last twelve years helping senior management teams and Boards to adapt to the new exigencies of the digitally enhanced marketplace. He has worked with world-class organisations to help activate their brand strategies, and figure out how best to integrate new technologies, digital tools, devices and platforms. Above all, Minter works to catalyse a change in mindset and dial up transformation. Minter received his BA in Trilingual Literature from Yale University (1987) and gained his MBA at INSEAD, Fontainebleau (1993). He’s author of four award-winning books, including Heartificial Empathy, Putting Heart into Business and Artificial Intelligence (2nd edition) (2023); You Lead, How Being Yourself Makes You A Better Leader (Kogan Page 2021); co-author of Futureproof, How To Get Your Business Ready For The Next Disruption (Pearson 2017); and author of The Last Ring Home (Myndset Press 2016), a book and documentary film, both of which have won awards and critical acclaim.

His current work is around fostering more meaningful conversation, with his featured publication on Substack: Dialogos, Fostering More Meaningful Conversations. It’s easy to inquire about booking Minter Dial here.