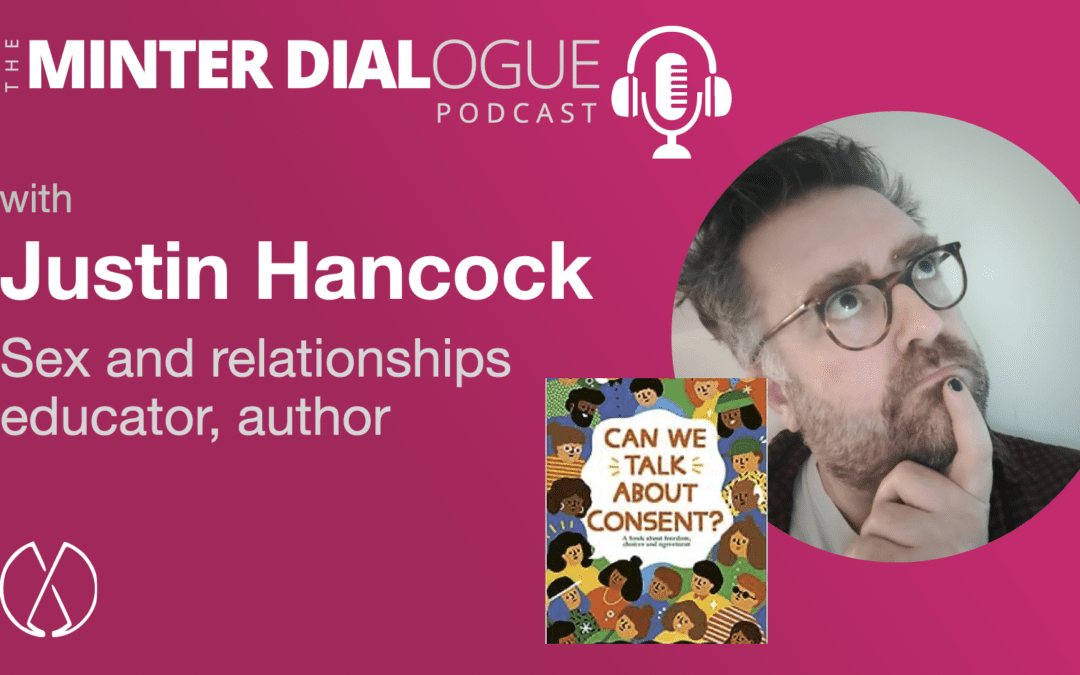

Minter Dialogue with Justin Hancock

Justin Hancock, based in England, has been a relationships and sex educator for over 20 years. In that time he has worked with thousands of young people in schools, youth clubs, universities, and advice services. Justin created and still works at bishuk.com which is one of the leading relationships and sex education websites for young people over 14, this site attracts thousands of people per day. Justin provides training courses and RSE resources for teachers. He offers relationships and sex education for an over 18 audience too. He wrote ‘Enjoy Sex (How, when and IF, You Want To)’ with Meg-John Barker, with whom he records the ‘Meg-John & Justin’ podcast, and most recently published “Can We Talk About Consent, A book about freedom, choices and agreement,” published by Frances Lincoln Children’s Books in 2021. In this conversation, we look at the state of sex and relationships today, typically among the younger generations, the decline in reported sex, toxic masculinity, me too, the rise of mental health issues, and how to broach consent, especially in a work environment.

Please send me your questions — as an audio file if you’d like — to nminterdial@gmail.com. Otherwise, below, you’ll find the show notes and, of course, you are invited to comment. If you liked the podcast, please take a moment to rate it here.

Further resources for the Minter Dialogue podcast:

Meanwhile, you can find my other interviews on the Minter Dialogue Show in this podcast tab, on Megaphone or via Apple Podcasts. If you like the show, please go over to rate this podcast via RateThisPodcast!

And for the francophones reading this, if you want to get more podcasts, you can also find my radio show en français over at: MinterDial.fr, on Megaphone or in iTunes.

Music credit: The jingle at the beginning of the show is courtesy of my friend, Pierre Journel, author of the Guitar Channel. And, the new sign-off music is “A Convinced Man,” a song I co-wrote and recorded with Stephanie Singer back in the late 1980s (please excuse the quality of the sound!).

Justin Hancock transcript via Otter.ai

SUMMARY KEYWORDS: consent, sex, people, talking, word, justin, relationships, kinds, sex education, women, hug, experience, create, work, young, sexual, happening, greeting, attention, culture

SPEAKERS: Minter Dial, Justin Hancock

Minter Dial

Hello and welcome to Minter Dialogue, episode number 536. My name is Minter Dial. And I’m your host for this podcast, a proud member of the Evergreen Podcast Network. For more information or to check out other shows on this network, please go visit our site, Evergreen podcasts.com. So, this week’s interview is with Justin Hancock. Based in England, Justin has been a relationships and sex educator for over 20 years. In that time, he has worked with 1000s of young people in schools, youth clubs, universities and advice services. Justin created and still works at bishuk.com – that’s BishUK.com, which is one of the leading relationships and sex education websites for young people over 14 and this attracts 1000s of people per day. Justin provides training courses and RSC resources for teachers. He offers relationships and sex education for an over 18-year-old audience too. He wrote the book enjoy sex, how when and if you want to with Meg John Barker, with whom he records the Meg John and Justin podcast. And He most recently published, “Can we talk about consent, a book about freedom choices and agreement,” published by Francis Lincoln children’s books in 2021. In this conversation with Justin, we look at the state of sex and relationships today. Typically among the younger generations, the decline in reported sex toxic masculinity, me to the rise of mental health issues and how to broach consent, especially in a work environment. You’ll find all the show notes on Minterdial.com. And if you could just spare a moment, go over and drop in a rating and review. And don’t forget to subscribe to catch all the future episodes. Now for the show.

Justin Hancock, you are a different kind of guest for me. I’m really looking forward to exploring what you’re up to and what you write about. Justin, in your own words, how would you like to describe who is Justin Hancock?

Justin Hancock

I’m a relationships and sexuality educator, working with young people and adults online and in person since 1999. So, kind of been doing this for a long time now, I guess.

Minter Dial

You certainly have. So, tell us, Justin, how you got into this, what was your path into this, this field?

Justin Hancock

Through youth work. So, I was doing a degree in law for some reason. And but during the summer holidays, I was working with young people. And I kind of thought, well, I enjoy this more. And there are many barriers for me being a lawyer as well. So, after I graduated, I trained with Derby City Council youth service. And they gave me really excellent training on how to work with young people. And then as part of that training, I specialized in working with young men around masculinities. And that led to me getting a job working with young men around masculinities, and sexual health and relationships in 1999. And that’s how I got into it. Since then, I’ve been working for various charities, local authorities, and I’ve been completely freelance since around 2014. delivering training courses. But, also, I run a website for young people called Bish which is visited by 1000s of people a day. It’s one of the leading sexuality education resources online. And I also have my own podcast culture, sex relationships. So, it’s kind of all led to all of that. Really. Yeah.

Minter Dial

It sounds great. Being trained as a lawyer, how has that informed or changed the way you’ve dealt with things? I mean, assume you, you have some kind of fidelity towards what you did in law and how much that makes you think about the small print and everything?

Justin Hancock

Yeah, not really. Yeah, I mean. Yeah, I did a law degree. So, I’m not trained as a lawyer. But I suppose what I think what degrees do and what any education does is to is to teach you to think and to teach you to learn. I think that’s the thing that I took away from it. I think there’s some interesting stuff there about intentionality and mens rea, or in the criminal law and things like that, which I think I definitely can’t take him with me. And causation is really kind of interesting kind of, I was mainly interested in the criminal law, sadly, is only a very small part of everything else. I’ve found really till sadly sorry, 20 One who’s a legal scholar who’s listening who really, really enjoys it. But yeah, it hasn’t really been super relevant apart from when I write and talk about the law and sexuality, which can be very complex and very tricky. And there’s a huge difference between the law itself, but also how the law is implemented and how, for example, Crown Prosecution. service guidelines differ to the actual written law about things like Sexual Offences Act 2003. But yeah, apart from that, it’s not really equipped me for a career in sexuality education.

Minter Dial

I’m possibly gonna get back into that when we talk a little later about contracting after consent. But let’s say over the last 20 years, it seems to me that we’ve had a lot of change that has under result been seen in society, especially in the West, I suppose, with regard to sexuality and sex, how would you describe where we are today, compared to when you began in 1989?

Justin Hancock

I think in some ways, there’s been a huge amount of change. And so, in other ways, there’s been very little change. I think, certainly the culture around sex. So, I think within that timeframe, we have experience, what we will call sex positivity, which is a response to what people regard as sex negativity. And I suppose because shorthand for sex negativity is for, dear listener, if you’re thinking about your own sex education, if your sex education was sexist about penis and vagina sex, and it’s about reproduction, don’t get pregnant, here are some gory images of sexually transmitted infections is something only adults do, don’t do it. It’s very bad for you. That is a lot of people’s experience of their own sex education. And I think a useful shorthand for that is what people just call sex negativity, where sex is only about reproduction. But it’s not about pleasure. It’s not about it barely talks about relationships. It’s very kind of mechanical, but only biological and mechanical about a particular kind of reproductive act. consents never mentioned, talking about sex is never mentioned. And people are left with a feeling that it’s a shameful topic that we shouldn’t talk about, and that and so therefore, people aren’t given the vocabulary or the confidence to be able to talk about it. I think in that time, we’ve seen sex positivity. So, pioneers of this I’ll probably shows like Sex in the City, which I like to hate on for. Because it’s, it’s a flawed show, in many ways. But it’s one of those key kind of pieces of media that that really kind of set a benchmark for a new way of talking about sex. I think we’ve seen that in lots of other ways in society. And I certainly think that there is a feminist element of that, where we’re trying to get women to try to allow women or invite women to be able to have their own kind of sexual subjectivity. And I think which is really good and useful. And I think we’ve had really important conversations about consent more recently. And I think people wanting to think more critically about relationships, and to think differently about how they do relationships. I think that’s certainly been the case over the last 20 years. But the things that haven’t really changed, I think, are we still have this very strong hetero normativity, this expectation of the that you’ll have, that you’ll be heterosexual, I think that is changing, but we’re still have it, I think we have a lot of non-normativity as well about what really what what counts as real sex, and still very, very strong social sexual scripts that people find very tricky to navigate still, and because of our lacking sex education, people still often find very tricky to talk about, and, and there’s a lot of shame and stigma around talking about it. So, I think we still have that too. So, there’s a long way to go. I still certainly have a lot of work to do, along with everyone else working in this field.

Minter Dial

I can only imagine. But let’s What about from the you typically tend to work with younger but I mean, you obviously work with older as well. But the in the younger field, I have two children 26 and 24. So, I’ve sort of gone through the younger period. They’re now sort of full -ledged young adults. Over the years, how have you seen the discussions you’ve held with 14 to let’s say, 18-year-olds, how has that changed?

Justin Hancock

Well, one I was talking about this the other day with somebody. So, it’s, it’s fresh on my mind. So, I’ve worked a lot with young men over the years, and 20 or so years ago, it would be quite common for me to hear from young men. I don’t care whether she’s enjoying it, as long as I’m enjoying it. That’s all it really matters. And now, I never hear that I’m much more likely to hear just in how can I make a cup? How can I last longer? How can I have better stamina in bed? And how can I be better at it? I think that both problematic because they are kind of, they’re still both kind of centering the, the man’s experience. So, the man is the subjection of the woman as the other. But I think it’s a different kind of subjectivity that they are wanting to do this thing of giving an orgasm to the woman as if that’s something that kind of belongs to the guy. But I think that that is a still problematic, but I think it is a big shift. And I think that speaks to the sex positivity that I was talking about earlier that there is this kind of a greater acceptance and a greater expectation and pressure for people to experience pleasurable, orgasmic sex. And I think that people find it very difficult to navigate both of those things. And I think the approach that I tried to take, which is the one that I took with my co-author of my first book, enjoy sex, however, if you want to my co-author was met John Barker, I think the kind of the position we tried to take was to, to be what we called Sex critical. So, where we try to encourage people to see the messages that they receive in society and these kinds of dominant kinds of discourses, and to critique them, but also to try to make sense of them. And to use what Michel Foucault would call technologies of the self, where we, we gather our, our various sexual knowledges, and our various experiences and are listening to our own body and, and being in tune with that with ourselves and our desires? How can we use that assemblage of things in order to create and recreate our own sexual versions of ourselves? I think that’s the kind of approach that is the most useful, because it is about resourcing, it’s about giving, it’s about giving us a using our kind of own experience and our own sexual knowledges. And the things we pick up as, as resources, rather than simply being told what to do by, by people. I think that’s the kind of that’s the approach that I think is the most useful, and the one that Yeah, I think, the most valuable and most useful?

Minter Dial

Well, it seems like it’s pointing towards the idea of self-responsibility.

Justin Hancock

I think it’s, we’d certainly try not to, and I certainly try really hard not to kind of individualize people. But I think that there is a degree to which sex and relationships are, and how we feel about ourselves are kind of private things which have been privatized, which is complex. So, you know, we talk about sex as being private, which I think a lot of people still consider it to be, you know, it’s kind of can only be talked about in certain forums. And, and certainly, not everyone wants to hear about it. But then that there is also in addition to that, it’s been kind of privatized by the, the messages we receive in society about sex. So, if we’re told when we’re when we’re younger, that sex is shameful, shouldn’t really talk about it, and any sex education we receive leaves us feeling awkward or uncomfortable and shocked, then, that further privatizes it which means that it does become it does end up being this kind of individual kind of like tussle, this kind of this kind of solo quest to discover our own sexuality. And actually, if we’d have had a better sex education, and the thing that I tried to do is if we have the tools to be able to talk about this with other people, then we will understand that our idea of ourselves can only exist in relation to other selves, and that we aren’t these individual atomized units that we all exist in relation to into everything else, and that we are an assemblage of lots of different things. And I think that that also is the crucial way forward to kind of make people look outwards for or to facilitate people looking outwards for connection and understanding and becoming rather than inwards for some kind of lack, or an essential story of themselves.

Minter Dial

interest interesting. So, the way I, Isa I would approach this interview with you Justin was to think about also the changes have happened at a societal level. And to see to what extent there are links. I mean, there are two statistics, I don’t have the exact details, because it varies from country to country, but very well documented that we are having less sex, at least according to whatever definition that surveys come with. And, second of all, we’re having less children in the West. So, let’s call that a heterosexual terrorist, typical type of statistic, yet I have to believe it, there’s a link with the work that you’re doing. And I wonder to what extent that those phenomena impacted you, and what are you seeing in your therapy in the work that you do?

Justin Hancock

Yeah, I should just don’t do therapy. Just as a disclaimer, though, folks. I call myself therapist, but I’m an educator. But, yeah, a couple of really interesting questions. I think that on the first point about people having less sex, the study, I get my go-to study about this in the UK is the NATSAL study, which is a huge academic study, which was done every 10 years. It’s extraordinarily rigorous. And there’s another one, there’s another one due out now. COVID delayed it, the last one came out in 2011. And it’s usually done over 10 years, there have been three iterations of it. And we’re all very excited about NATSAL v4, come on NATSAL 4. And with us, today, we’re finding that people were having less penis and vagina sex. But they were possibly having more different kinds of sex. That kind of that did seem like there was some evidence that there was a broader repertoire of sexual activity. So, perhaps people are having less sex, but more sex that they want more intentional sex, more sex, or sex for sex’s sake, more sex for pleasure. But also, perhaps people by not having sex, or having a better time, you know, there’s a lot of sex can be really bad, and particularly if it’s, if we’re just following sexual scripts, doing it, because we think we owe it to suck to our partners, you know. And so, I think that what I was talking about before the kinds of the increasing understanding of the role of pleasure and how we might have it, and how this is a, this kind of thing of being embodied, being feeling a bit more sexually empowered, I think might well could understandably, results in letter but better, better, sorry, less, but better sex, or less but more enjoyable sex or, or just different kinds of also, it depends on the study, doesn’t it as you say, so, you know, some studies might not see having a snug as being sex, but I think they should. Because having a snug is deeply sexual, and can be incredibly pleasurable.

Minter Dial

Well, it also we need to clarify for the non-English speakers because they’re not British, because snug is quite a British term. Yeah,

Justin Hancock

I use very British terms all the time. Yeah. Open mouth kissing or French kissing. Yeah. In French, I think it’s called galocher. But we only call it French kissing as well.

Minter Dial

The idea of less but better. I also have other things which are in my wheelhouse, which I typically look at, which is the vast increases of anxiety declared anxiety and depression, specifically among the younger generations. So, I can’t equate with that a, an uptick in happiness or in better mental health. And I wondered to what extent the issues around sex have played a role in this increase of anxiety and depression.

Justin Hancock

Well, I think there are a lot of things that are connected here. I think that if people have anxiety and depression that can, it often means that they are less likely to be able to enjoy sex. But also, if it’s about putting the cart before the horse, so sometimes if people are less able to enjoy sex, that might also have an effect on the mental health too. So, I’m not trying to draw any kind of dry direct lines of causation or anything like that. But I think generally, if we’re talking about anxiety and depression, I think we also have to kind of consider the material impacts that are actually that have happened. And not to sound like a, you know, the left-wing nerd that I am, but the life is harder for a lot of people, particularly young people, and particularly, during COVID. You know, COVID really heightened a lot of pre-existing mental health problems. And so, I think that we, you know, looking at, you know, so I was talking about the diversity council youth service the other day, the other day, earlier in our conversation, where I received my training. And, you know, they had youth clubs, and projects all over the city, including the specialist health specialists, Youth Work team, people like me, who go in and do stuff around sexual health and relationships, but also other kinds of specialists kind of education as well. None of that exists anymore in the same way. And that’s true for a lot of places around the country, that the, the lack of things for young people to do outside of school, is really quite stark. And so, if there are fewer places for young people to spend time with each other, face to face, making connections and socializing, and also being able to access support and resources from each other, but also people like youth workers, then that is going to have a knock-on effect on people’s mental health. But also, the lack of space generally, for young people, I think, you know, so many areas in geographic areas have been kind of privatized places where young people can just kind of hang out, much more heavily monitored and controlled. And so, I think that plus the pool of mobile phones and internet, laptops has kind of has shrunk a lot of young people’s lives, I think in ways which certainly I think are part of the assemblage that we need to talk about when we’re talking about mental health and young people. I also do think that there’s something here about the discourses of anxiety and depression, being sometimes unhelpfully talked about in ways where, where instead of thinking about what might we do to feel better about our mental health and to feel better, and what are the kinds of ways in which we can connect with others, that might kind of be really good. I think that when we sometimes when more broadly, we’re using the terminology of diagnosis, that I think that sometimes it mean, it leads people to kind of holding on to the diagnosis, rather than thinking about what a diagnosis might do. And so, I think that it is a sometimes I think, it has a kind of reverse effect, where, where, instead of instead of thinking about, well, if I got some treatment around this, or I was able to access a talking treatment about this or to be able to get some other kind of resource or support. It might help me do dot, dot dot. Instead, I think sometimes people, people would perhaps talk a little bit too much about the diagnoses or the or the problems rather than the potential solutions. But also, having said that, there are material factors there too. So, the waiting list for child and adult child and adolescent mental health services in the UK, known as CAMHS, is huge, it’s a massive waiting list. So, the ability for young people to find support, it has vastly diminished, as well as the possibilities for young people’s mental health to thrive because of the closure of lot of spaces that young people could have or to access. So, I think all of that is kind of involved. And of course, you know, I guess it’s harder for people to to connect if they, if they’re only if the only space where they can connect with other young people is in school, college university or Lesotho university because school or college then and it gives you a very quiet small window in your day where there is the possibility for making friendships, experiencing chemistry with people flirting with people or you know, just kind of you know, the, the everyday business of what I call it my website, my quoting from that Professor Barbara Fredrickson, psychologists working in the US, micro moments of positivity resonance, so Micromax sense of positivity resonance are those things that happen on a daily basis where you have a glimpse of a bit of eye contact with someone or something makes us smile or kind of have a little fuzzy feeling from like an interaction with someone at a shop or going someone with a dog and you know, stroke their dog and say hello to the owner, or you know, those kinds of everyday kinds of things, if we reduced the possibilities for micro moments of positivity, resonance, which other people call falling in love that I like to call micro moments of positivity resonance, then we are reducing the possibilities for people to become and to emerge. And, but also sorry, I’m ranting. The other thing about school is, and college is that young people are under so much pressure to get grades to become this ideal neoliberal subject who is in a very successful at school, and can get a job in a marketplace. And so, you know, to do a university course, which is going to be good for their career, there’s so much pressure on young people to not fail. And I think that a lot of playfulness, and a lot of the potential for soft skills. And a lot of the potential for connection has been stripped out of young people’s lives in ways which no one asked for, and in ways which we don’t fully understand how detrimental they’ve been. My thinking that way. It all, it all kind of connects to sex and relationships or sexuality and relationships, because not so much the act of having sex, but just the possibilities of seeing people and flirting and having these kind of micro moments of people being a, this joyous activity we do with other people, this collective joy, a joyous effect to us, like an academic term. And so, I think that’s the kind of broader picture. And that’s how that’s how I see all of these things kind of interacting with each other. Yeah.

Minter Dial

Well, lots of things in there, Justin, I was piqued by this notion that the opportunities for young to, to meat is reduced, and nobody has asked for it. I’m not sure. I feel like there’s this principle of precaution. That is imposed by the ask of parents, I don’t want my child to be out in the street, because it’s dangerous out there. And you better put on a mask because it’s dangerous out there. And better not hang with them because they’re dangerous. And so, I feel like it it isn’t by mistake, if you will, this idea that privatization is perhaps a new argument that I hadn’t thought about, but I definitely see society unwilling to let go, you know, of, because I only have one child, right? You know, and now every, that’s my prince or my princess, and they need to survive, because I don’t have nine other off offspring to help through. And otherwise, my genes will not continue. And there’s so I think there’s a lot of intentionality behind this notion of, of not getting together with others. And the harder piece, I mean, we live in, I mean, amazingly progressive, advanced times. And so, it’s hard for me to think of all these mental health issues coming up, without thinking that there’s a causality with with our, you know, worry about this worry about that. Our that, frankly, in the way I see things, there’s been a lot of reduction of our ability to speak, because it can trigger so you have to be particularly careful about any words you use. And in that, there’s another piece, which is, well, are you flirting with me? Or is that that’s dangerous? Can let’s have consent about flirting? And if we have to contract all these things, and eliminate words, as any lawyer might from any contract, it makes for difficult dance and creating positive relationships.

Justin Hancock

Yeah, I certainly have heard this from young people, too. And adults. And I think what we’re talking about here is consent. And I’ve written a book about this. Yes,

Minter Dial

which is why we’re into it.

Justin Hancock

And that’s just excellent hosting there, to get to talk about the book. You’re a pro. The issue is the way that consent has been talked about and utilized and, and the effect that that’s had on young people. So, nowadays, if I go into a school and say, All right, we’re going to do a lesson on consent, everyone On just groans and folds their arms and hates me for a minute. Because they think that what they’re going to be told is yes means yes, no means no, you always have to ask first before you do absolutely anything, and that men are potential perpetrators and women are potential victims. And the women and the men and non-binary folk, eight concern now they hate talking about it. Because of these, I get quite wound up about this, because of the infantilizing and stupid and moralizing and legalistic and black and white binary way that it has been taught. The way that consent has been taught, has been this top down approach where it is it has been policymakers. And some educators who think Well, of course, I know what consent is, I’ve never done anything non-consensual in my life. But as these others who don’t really understand, so I’m going to give them this message, I’m going to tell them what consent is, and why they should do it and why it’s important. And we’re going to save future generations. And actually all that is done as to make people feel, as you say, anxious, under resourced feeling unable. And feeling like consent is a barrier that have to get over in order to do something, which creates in and of itself, much more harmful outcomes, which are non-consensual. So, often what happens is people might pass to somebody for a yes. And then once they get that, yes, everything else seems to be fair game. And so, we have this really problematic kind of discourse about consent, which has produced this binary thing of men have to as reproduce the binary, the the reproduces gender stereotypes and really problematic ways that there’s always one person has to be the asker. And the other person who has to be the giver of permission, one person is the gatekeeper, and heterosexual relationships. That is, you know, the man being active and the woman has to be passive. And in same sex relationships, that the idea that there always has to be a top or a bottom, or someone who is the the confident one, who is sexually experienced and somebody who isn’t, rather than consent being this assemblage of actions, and which can be words works, but also our bodies, and how our bodies interact with each other, which have the possibility of producing collective joy. So, rather than consent being a barrier to get over, I think that we should start seeing consent as the things that we do to really enhance having a great time with someone, and how do we have how do we maximize the possibility of having experiencing joy for ourselves and with someone else. And all of the things that we do in our everyday lives to do that is what consent is that is the worker consent. It’s ongoing, it’s fluid, it’s iterative, it’s generative, it’s co created. And it’s constant. And the act of doing concern in that way, can be incredibly joyful. And so, I think a really good way of thinking about this is to think about nonsexual examples, because I think that really helps us to, to figure out where what we’re talking about here. So, one example that I like to talk about a lot is imagine someone’s coming over to your house, and they’re gonna watch TV, and you’ve got all the streaming services, okay, who holds the remote? How do you figure out what it is you’re gonna watch? What are the kinds of conversations that we might have to make someone feel comfortable enough in order that they can say, I’m not really in the mood for this, or I’ve seen this before? Or these kinds of things scare me or there are certain things I can’t watch? You know, for me, I can’t alter anything with injections in like lots of TV and films, I’ve injections and inevitably, so that’s my kind of thing that I would say to a friend. How do you make the the comfortable environment where you can both have this conversation? What kinds of conversations might you have before about it? What kind of conversations might you have about the motivations like what you want to get out of evening? Are you there mostly to chat or are you there mostly to watch something you know, if we are going to watch something, how seriously are we going to watch it or we’re going to watch it you know, with subtitles on, really pay attention to everything, or we’re going to have something on the background work and kind of take the piss out of something and watch it a bit like they do on Googlebox the UK reality TV show, which is excellent. Everyone should watch it. It’s really really good. And how do we if we’ve agreed on shirt we’re going to watch with somebody you know, just talking about you dear listener when you have a friend over here watching something with anyone. How do you kind of figure out whether you and the other person is enjoying it? So, are they laughing at the funny bits? Are they hiding behind the sofa? Scary bits Are they just kind of yawning? Are they checking their phone during it? Are they just kind of looking disinterested or talking about something which clearly isn’t the TV? And what kind of things might we do in order to check in as we go? So, you know, when we press pause when someone goes to the loo, or gets a drink, or some popcorn or whatever, we could say, oh, how feeling about this is still okay, you know, should we carry on for another episode and see how it goes? Or should we try something else? You know, these are the kinds of things that we do. None of that is radical. It’s the things that we’re all doing in all aspects of our lives, this kind of thing. But all of that is it’s this perseverance of sometimes slightly awkward conversations. But we’re persevering in order that we can both experience joy. And we do that in all aspects of our life. And the thing that we don’t teach young people. Well, I teach people this and other good sex educators teaching people this. We think that somehow when it comes to sex, sexual consent, we have to say, yes means yes, no means no, get everyone’s agreement before you do something. And then, and then you can just kind of do it, and no other aspects of our lives do this apart from things like contractual things. So, saying, clicking the Yes I accept all your cookies on a website? Or clicking Yes, I understand the terms and conditions, that no one ever reads the terms and conditions, or Yeah, quite, you know, ticking a box, you know, that kind of consent is the way that sexual consent has been talked about. And so, it’s no wonder that because young people have been taught about consent in that very narrow, legalistic terms or conditions, tick a box contract kind of way, that they’re all pissed off about it, and don’t feel like it can help them. And really what consent does, is facilitates a really great time. And if we all talk about consent in that way, then I think we’d actually just have a better time and there’d be more joy, there’d be more possibilities for collective joy. I just genuinely believe that.

Minter Dial

I don’t want to get into that. There are so many other things that I’m my mind is percolating on. You mentioned the self-technology of Michel Foucault. I can’t help but think since we haven’t addressed it, there are other technologies that have impacted heavily, this notion of consent, and what is sex in the form of online porn and dating apps. And, and I, and I suspect that in the latter, the this, the legal elements within it somehow have constrained the freedoms. I mean, I at some level, there’s, it appears to open the freedoms. But there’s a whole lexicon and there’s a whole how to and to use your word, that’s how you should present yourself it feels in these dating apps. And then I been hearing — my daughter studied psychology at St. Andrews. And, and we have lots of conversations about how it is on campuses in the United States, for example, where this notion of contracting is almost important for the purposes of safeguarding any act before — as my son experienced — where two friends were expelled. Just because the woman in particular said that this person aggressed her because he took advantage of her because she had had a beer. And there was no other witness or anything else. And it was just under the premise that one person says the other person was horrible. And then there’s no court system, it’s just you’re out. So, somehow, this contract, and I don’t want to talk about it as a lawyer, but this is where it comes in. We’ve come to a position where in order for masculine toxicity to be eliminated from the equation, me too not to happen. There’s a need for men to safeguard themselves by saying or at least in the men, you know, heterosexual, so to speak, elements, that they have to safeguard themselves by saying, Are you sure you really want to do this? Because if you don’t want to have a post, a post sexual intercourse will, you know, I’m, I’m back in the I’m having problems.

Justin Hancock

Okay, so the way I covered this when young people asked me about this, and it’s usually young men who asked me about this, you know, how do they kind of had to kind of almost prove that everything was consensual, right? I can understand why that is. I can understand why young men feel anxious about this, but the way I respond to this is to I repeat to them what the Crown Prosecution Service in the UK guidelines say. And so, under a police interview, if you’ve ever got as far as a police interview, what the what the prosecution would want to see is would want to ask the accused is, well, what steps did you take to make sure that it was conceptual? What were you doing to make sure it was conceptual? And that could be any of the things that I was just talking about, about the someone coming around to watch Netflix? So, you know, did you check in? During it, you know, during, during any kind of sexual activity, where you like, you know, how did you were you kind of, you know, that could ask, like, where you’re mirroring each other? Or what were the kinds of activities you were doing, were you kind of slowing down at various points in order to allow their body to move towards yours, were you noticing any elements of passivity and just like, just kind of stepping back and saying, perhaps they’re not really ready for that, if they have been drinking, you know, I checking in about how, how far they kind of want to go and, and, and, and, but all of these things aren’t necessarily verbal, that we use our bodies to do this to, and that we’re picking up on everything that is happening in that moment, the vibe, the atmosphere, the, you know, what been said before what had been leading up to this, what happened afterwards, the nature of the relationship. And, but also, it’s, it’s very uncommon for, for, for these allegations to be false. Like sometimes these allegations aren’t proven, but it’s very uncommon for these allegations to be false. And convictions for rape and prosecutions for raping the UK are incredibly low for lots of different reasons. And I think the criminal justice system is, and criminal justice models, the kind of legalistic models around consent, don’t serve survivors and victims very well at all. And we’ve I think we’ve learned very little about justice from during that kind of, I don’t want to say post me too, because we’re still in Metoo. So, in the each metoo era, I think we’ve learned very little about consent and, and justice and accountability and, and gendered violence. And I certainly think that these kind of narrow, legalistic models that I’ve been talking about have not only not helped, but made it worse. And I think that this is where we need to pay attention to this thing that I’ve been talking about, which is the consent as it actually exists, rather than the consent we talked about. And that is about talking about the things that we do to make sure everyone’s having a good time. And these are kind of micro communications that we can all just start paying attention to in all aspects of our lives. And then when we pay attention to them in all aspects of our lives, we can help them to come to life when during sexual or intimate encounters to. But certainly, yeah, as I’ve been saying, I think that when it comes to sex, we sometimes teach, you know, we teach this kind of this kind of very different model of consent, which I think is just really not helping people at all.

Minter Dial

So, Justin, we were talking about consent and, and I was having a fun interesting chat with my daughter who’s studied psychology at St. Andrews, about the notion of stop, which you address in your book about consent typically mean for the younger generations. But she brought to my attention, a term, which is with new to me, which is a safe word, is in replacement of stop. So, instead of saying, Stop doing that, when you’re moving into a church, you don’t want to do use another word, and she talked about the word avocado or something like that. And that allows for both to understand that this is, you know, in this context stop. Tell us about how or what you think of that.

Justin Hancock

Yeah, so the idea of safe words really just came from this very specific kink, which is called consensual non consent, where people might roleplay something which in which in, which might be a fantasy of a non-consensual sexual activity. And so, the word STOP there wouldn’t necessarily mean stop. They’d have to use a different word there’s so they would have to use the word avocado if they actually meant okay, I didn’t actually need to stop now. Because the word stop in a consensual non-consensual scene is part of the scene, if that makes sense. So, a safe word that are like avocado is incredibly important, because you do need to be able to say, Oh, now the scene actually has to stop. So, avocado, banana, pineapple, people often use fruits, avocado, the fattiest of the fruit. arguably every grapefruit I’m not a fan. So

Minter Dial

I didn’t say mushrooms at least!

Justin Hancock

Yeah, I’m allergic to those. So, yeah, so I think that’s where safe words comes from. And safe words has also become this thing, as your boss was saying, outside of that scene, but the research kind of does show that people don’t use when people want things to stop, or when people say, No, I don’t want to do something, people often don’t use those words. In fact, people might not use any words, but people do kind of pick up on that the other person does also pick up on or is able to pick up on the fact that somebody wants something, something to stop, or doesn’t want something to happen. Three, the other words, or the gestures, or the science. And so, I think that there is a, I can understand why it is that people might want to bring the word avocado into their intimate lives. But there’s a danger where avocado just becomes another word, which is sometimes it’s difficult to say a stop or no, because when that word has those kinds of meanings within that specific context where you’ve discussed it, it can still be quite difficult to say. And so, if we create this one word, which where there’s a lot at stake, if we say it, if we change that word, it this, the stakes are still high, if that makes sense. So, it doesn’t take away any of the things in my view, it doesn’t take any, it doesn’t take away the difficulties, or saying the word, it just gives us another word, which you might find difficult to say. And so, what we need to take into account here are also potential, you know, power imbalances. Who wants to have sex the most, what are the motivations around having sex, the nature of any kind of sex being co-created, and how mutual whatever is happening is going on. Also, this thing of how important it is to just be really attentive, and to be to try as hard as possible to be in the moment in your bodies, paying attention to the other person in their bodies in the moment. And that means paying attention to all of the different things all of the different ways we communicate words, noises, breathing, how, you know, flinching relaxation, stiffness, or a relaxedness. But also the vibe of you know, we will pick up on the vibe of the room, the atmosphere? are we feeling any pressure from anywhere else? Both from our past from what was happening before? Or what’s happening in the context of the relationship? Or what’s happening for the context of us? Generally? are we feeling relaxed enough? Is, is there enough time in all of these things are really important factors in, in in trying to maximize consent and maximizing joy? In those moments? So, I think we need to go beyond words, whether that is yes, no stop or avocado.

Minter Dial

So, I want to end just in talking about this notion of consent in a workplace environment. I think it’s an interesting way to explore interesting conversation. And the context I wanted to draw out, which I know is featured in your last book about consent, which is this notion of greetings and the hugs. So, I worked at a company back in the 1990s and the early 2000s, where we had, as a culture, a notion of hugging, but not just any old hug, a long embrace. And so, and this was man to man, woman to woman and men to women. We called it the Redken Hug. Right? And this hug was literally five, seven seconds sort of thing. And, and the idea behind it was well: this is how we are. We set it upfront. This is sort of part of our culture. And if you’re not comfortable with it, then that’s okay. If you weren’t into the hug, it wasn’t the kind of thing you’re in or out on. But we had a whole set of codes about how we discuss how we operate, how we behave. The words we use when we are discussing, for example, the hair because this is what we’re talking about in particular. Yeah. And bear in mind that this is the hairdressing industry. Today this is completely in 10 tenable, you wouldn’t you get laughed off the street or screened out Yeah. And then So, then I was I’ve talked to the few of my ex-colleagues about this notion of where the hug is in society, post COVID. And all that. But let’s is just help us out with this idea of let’s consent on some cultural activity. That is we feel as part of ours. And it could also be if I’m Korean, about the Korean way, or the Russian way where they kiss on the lips, you know, where men kiss on the lips. Or the French way where you come in and men handshake and the women and men and women and women are all give two kisses when the cheeks.

Justin Hancock

Yeah, or three or four, depending right isn’t part of France you’re in…

Minter Dial

Or the three and a half, you know, where are you in the middle of the process.. Oh, shit, I landed on the lips this time. So, talk about how does one go about in a business environment, talking or using the consent avenue to bring into work?

Justin Hancock

Yeah, well, thank you, again, for teeing me up. If you run a business out there, folks, and you want me to come in and do a workshop with you. And we’ll happily do that get in touch? Yeah, so I’ve been teaching about consent via teaching about how to have a really great conceptual greeting. And I found it so incredibly useful. And so, pretty much everyone who has done it, because again, rather than telling them what consent is, and why it’s important that they should do it. We’ve been learning through practicing how we might do a more conceptual greeting how might bring more consent, integrate things. And consent is something we can always have more of, rather than it being just that exists or doesn’t exist. And so, I think workplaces could have a, I think the issue is it’s about what you were talking about there with hugs is, is literally creating an organizational culture, which makes people do things that they might not necessarily want to do. And it almost kind of sets they written a script for exactly what it is that they should do. And I know a lot of people who really, really hate hooks who find hooks incredibly difficult. And so, I know a lot of people who if they’re working in that workplace might not have wanted to work there for very long if they have the option, because they would have found those hooks really hard, really, really hard. And so, first and foremost, organizations need to think, are we writing our own scripts? Are we telling our own? Are we creating short stories that aren’t good for the business necessarily, and are bad for the employees. And it’s just kind of like a lose lose or route? Are we in some ways, restricting people’s autonomy and people’s capacity for, for collective joy, as much joy as you can have in a workplace? By having these kinds of by having these kinds of cultures, like one culture around this, which I’m hoping this has changed this, you know, bear in mind also, I’ve been a freelance sex educator for many years. And even when I was not freelance i, we didn’t have an office, basically. So, it’s been many, many years since I worked in an office, but I know people who do still. And yeah, the after work, drinks culture thing, is, is another one that could be looked at, or, you know, because it’s often if that’s where key decisions are made, and where key relationships are made, then who does that exclude? And who does that? Who is you know, which identities are getting privileged in that respect. But it says of greetings. I think that what we could do is just to, before we have a greeting before we see someone just to slow it down a little bit, just like a second or two. And just pay attention to what it is that what kind of greeting they might want. If they’ve got their hands in their pockets, and they just want to do a nod, then maybe you could just step back and just don’t go in their personal space, but maybe just give them a little nod. Or maybe and hopefully they might do that to you too. If you’re going in with your with two hands. So, one hand it kind of like 10 o’clock, and the other hand, like four o’clock, kind of anti, you’re doing a bit of a lean looking like you’re going for a hug, and the other person is kind of nodding and they’re they’re 10 and four o’clock too. And then that means a hug is on the cards. And if you’re going to have a hug, can you pay attention to how firm you both want that hook to be during the hook? Can you kind of notice what kind of hook you’re having? Are you going to do the backpacks which you know, men often like to do to kind of somehow like make it a bit more masculine. I know I do that sometimes probably. Can you notice the any kind of sounds or you know, nice to see you or the kind of you know, it’s sometimes expressing a nice hook. And then can you notice the moment when you both want to To kind of disentangle from the hook and disengage from the hook. And then next is what you might be saying to each other afterwards or how that felt for both of you. And was there any kind of glimmers of joy between you, were you experiencing a micro moment of positivity resonance, where you know, you’re experiencing the micro moment of positivity, resonance includes various neurobiological things actually happening in your body. So, the vagus nerve kicks in and regulates your heartbeat, oxytocin kicks in to help you tune into the other person and your pupils dilate your hearing adjust to the frequencies of the other person, your neural pathways map onto each other lots of lots and lots of things happen in these kinds of moments, can you just take like a second, just to kind of acknowledge that a nice thing has happened. And that’s what a greeting is meant to be. A greeting is meant to be this nice little kind of way of introducing yourself to someone or saying hello to someone or to have this kind of a tiny amount of connection with someone which can feel really joyous, whether it’s a hug, a salute, a noncontact greeting of some description, a good old -fashioned handshake, or a fist bump. And again, this is, as you say, this is something we’re all exploring through COVID, we all had to figure out what the hell we were doing. Some of us still trying to figure that out, but some of us have just gone straight back into the script of, you know, what you’re supposed to do. So, we just think that, yeah, if we are going to encourage people to go back into workplaces, which I, you know, I’m like, I’m all for flexible, working with people working in offices if they want to, but surely, one of the benefits of being in the office is having people around, and having this possibility of these just little moments of joy throughout your day from just interacting with other humans face to face. I’m not saying it’s necessarily flirtatious, or, or in any way, you know, intimate or sexual, but just, you know, the joy of, you know, a colleague or a shared joke, or, you know, a kind of a smile across the office, you know, sometimes, obviously, sometimes I fantasize about what it might be like for me to be in an office, because I just work entirely by myself. And I sometimes think it might be quite nice just to, you know, have this, like, buzz of energy that from all of these little connected, you know, interactions. And so, I think for managers, and for anyone in charge of policy and trying to create a great office culture, I think that’s the thing to really pay attention to, is that, how can we, how can we facilitate these kinds of things? And how can we rather than enforcing a culture of everyone hooks, can we instead just say, or it’s just a commit, and that’s all just practice, and try to tune into the moment and be in the moment rather than going ahead and doing the Scripture thing. Because if we have this strong idea of a script, and we’re paying more attention to the script than we are the person, then we’re not really maximizing the possibility for consent, and we’re not maximizing the possibility for joy. And I think that would make a really much nicer office environment.

Minter Dial

Well, lots to unpack within that. But time is of the essence, Justin. For me, I’m an older guy, and I didn’t go into the military, but I’ve lived and worked in many countries, and I see the greeting as a not just a moment of joy. I see the greeting typically is a first regard, if you will, and who are you? Where are you? Is in is in that? You know, just like you look at a book in the cover your jet, you see somebody tall, small, big, whatever, you make judgments and generalizations and then my feeling is that, like flirtation, there’s so much that’s much more subtle. And if we end up having to de deconstruct every little micro moment, it can probably take some of the joy out of the moment. If are we flirting here? So, when you expose the flirt, it’s becomes wide-open? Does that make it better or worse? And me? Yeah, if I could just finish the last pieces. It’s maybe the discussion around this topic. That is the inciting or the insightful, the illuminating element to allow for this discussion in the boardroom, hey, what kind of habits do we have? Because I think it’s important to, to make decisions that not everybody’s gonna like, because trying to please everybody, all the time, everywhere means you, you become nobody. So, when you when you want to create a culture, the idea of doing everything and allowing everybody to be everybody all the time is an amorphous, non-delineated culture. It’s a non-delineated group, and therefore, it’s easy and easy out. Whereas when you have codes of behavior, in our company, this is how we do things. It’s not an illegal thing. But this is our tenant. This is our It’s about our values, and we express those values through this way, which means words we use, and you can choose to be more or less inclusive in that you can choose to be more or less affirmative or, you know, military and style. And for some that will suit and for others it won’t be, then that becomes the gatekeeper, as long as it’s well understood within the company.

Justin Hancock

Yeah, I mean, I think the I think we’re kind of agreeing and disagreeing here that I think that I think that we, I think the one thing that a boardroom could say to that would, that would improve the office culture in the office environment probably is, that’s all just paid for the really great attention. Let’s just be really attentive and kind and respectful. And we do that collectively. And rather than imposing like a code of this is how we’re meant to do things. And certainly, if you have to negotiate every hug verbally, before you do it, that does make it awkward, we practically do that as part of the activity I was talking about too. But just to just to slow things down just a little bit, just pay a bit more attention to bring the some of this really what we’re talking about here of care, and the value of care, and what we might call soft skills. And the ways in which this might, you know, kind of help facilitate this kind of this collective approach, where, you know, everyone is just, you know, like to kind of think about, you know, just when, you know, a football team is really singing, you know, when it’s hard for me, because I’m a Derby County fan, and they never seem to sing. But you know, when you see a really good football team, and just everything, you’ll never walk alone, by Thank you, you know, every pass is, you know, going exactly where it needs to be, they almost don’t need to look up to know, are players coming in from the other side? And the passes are pinging around like Spain versus England, sadly, in the final Women’s World Cup, yeah, you know, everything, you know, and they’re kind of on song. And it is a little bit like, I think that what I’m talking about here is about the pot, what how do we get that? How do we be in tune with each other and in tune collectively, and I think we do that through these tiny little micro moments of paying attention. What feels instinctive and what can feel like it’s kind of magic, and instinctive is actually just a series of microprocessors, we’re not really paying enough attention to. And so, I think in that way, that can create an assemblage where everything is kind of just on song, and everything just feels right. And just by paying attention, I think in that way, we can get over this idea of, of, again, I’ve not worked in organizations. So, I’m probably overreaching my expertise here. But I think that this idea of, instead of, it always seems to be that there in these kinds of discussions, it’s either is it horizontal? Or is it vertical? Is it horizontal, in terms of, should there be no hierarchy whatsoever? Should everyone just be kind of autonomous, autonomous nodes within this kind of horizontal system, where everything kind of gets figured out by consensus? Or is it vertical, where someone is clearly in charge, and everyone knows what they’re doing? I think that there is a, you know, to go back to a really great football team, clearly there, it’s a bit of both, you know, there’s a manager who’s facilitating everyone being really on song with each other and trying to create the vibe and the environment where they’ll trust each other and, and they can pay attention to each other. And through these kinds of acts of care and camaraderie and, and knowing each other, knowing each other’s strengths and weaknesses and everyone’s possibilities, and how everyone can bring out the best in each other. I think in that way, it’s both horizontal and vertical, and neither interest in kind of interesting ways. But it can just be done by really paying attention to the process, and really paying attention to the how of the how of doing things. And that is both. That’s both good for individuals, but also good for the collective and that, you know, that being part of that collective on song where everyone has a degree of autonomy, and also is doing this for and is part of this greater good. I think that’s kind of like a win-win for everyone. I think that’s what a lot of people I guess, and organizations try to achieve, you know, that’s like the magic kind of element. And I think that the way to achieve it is through is through this paying attention to, to, to culture and the kinds of things that we can get everyone to do to be to be more attentive and to be in the moment and in tune with each other.

Minter Dial

And also to know how to put down boundaries somehow. It feels like a we could open a whole other chapter We’re about talking about spiral dynamics, because what you were talking about feels very much like the interplay between me, we and everybody. So, there’s me the, the individual, there’s we this collective and everybody is everybody. And, and there’s a, there’s a need to define things within that. Because if you’re trying to be the horizontal, we love everybody, we take anybody. Well, good luck with that. And what is we? Well, we is some small group as a big enough, is it small enough and, and what is we and how do you define we? And I and I referenced I love to talk about semi patterns, but we in this particular regard anyway, Justin, we could surely and I love the fact that we end on a disagree and an agree piece. Great to have you on the show. How can people track you down, understand, read up about you and hire you? Maybe we all buy your books? Crucially, the best way is Yeah,

Justin Hancock

Yeah, I think just go to my website justinhancock.co.uk.

Minter Dial

And of course, there’s Bish and I’ll put as many little other links to your books and stuff in the show notes. Thank you very much for coming on the show again. Thanks for having me. Thanks for having listened to this episode of The Minter dialogue podcast. If you’d like to show would like to support me, please consider a donation on patreon.com forward slash Minter dial. You can also subscribe on your favorite podcast service and as ever, rating & reviews are the real currency podcasts. You’ll find the show notes with over 2000 and more blog posts on minterdial.com Check out my documentary film and four books including my last one, “You Lead, How being yourself makes you a better leader.” And to finish here’s a song I wrote with Stephanie Singer, A Convinced Man.

Minter Dial

Minter Dial is an international professional speaker, author & consultant on Leadership, Branding and Transformation. After a successful international career at L’Oréal, Minter Dial returned to his entrepreneurial roots and has spent the last twelve years helping senior management teams and Boards to adapt to the new exigencies of the digitally enhanced marketplace. He has worked with world-class organisations to help activate their brand strategies, and figure out how best to integrate new technologies, digital tools, devices and platforms. Above all, Minter works to catalyse a change in mindset and dial up transformation. Minter received his BA in Trilingual Literature from Yale University (1987) and gained his MBA at INSEAD, Fontainebleau (1993). He’s author of four award-winning books, including Heartificial Empathy, Putting Heart into Business and Artificial Intelligence (2nd edition) (2023); You Lead, How Being Yourself Makes You A Better Leader (Kogan Page 2021); co-author of Futureproof, How To Get Your Business Ready For The Next Disruption (Pearson 2017); and author of The Last Ring Home (Myndset Press 2016), a book and documentary film, both of which have won awards and critical acclaim.

👉🏼 It’s easy to inquire about booking Minter Dial here.