Being a “brand guy,” I tend to look at businesses through the lens of branding: what does the brand stand for? how strong is its brand?

But, what exactly is a brand? Can any/every company or business actually be a brand? How can one build up a brand?

In this post, I wanted to explore a lesser trodden path to get to the root of these questions.

So, what is a brand?

What is a brand? The way I look at it, a brand is a statement, a mark of trust.

A brand is a statement of ownership, intent and trust. #branding #brand #marque Share on XA brand scale

I believe it’s important to set out that not every company is a brand. Just because you own a trademark doesn’t confer brand status on you. While a company is looking to boost sales and turn profits, a brand also looks at different metrics and concerns itself with developing its true essence and providing value to a bigger community beyond its shareholders. Brands genuinely concern themselves with being lovemarks (as described by Saatchi’s Kevin Roberts) inside and out.

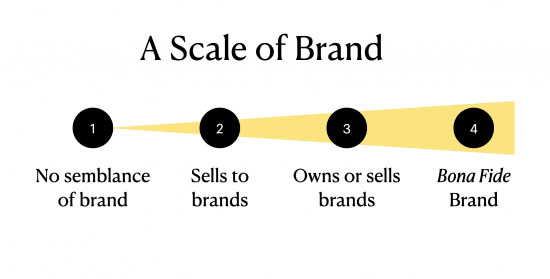

In my conversations and writings, I’m often making a difference between a corporation and a brand. Notwithstanding the many other possible formulations of a corporation (e.g. company, organization, association, charity…), there are many that do not warrant being called a brand. They are just an entity, bearing a company name, that is doing business, providing a service and/or selling a good. In the realm of branding and of being a brand, I think of it as a scale. I posit that there are four types of companies across this brand scale, not taking away from the fact that any company across the scale can succeed or fail.

- To the far left in figure 1, representing by far the biggest number of companies, they have no semblance of a brand.

- These are companies, like agencies or consultancies, that make money by selling to brands.

- Companies that own or sell brands, for example: a distributor, a retailer or a multinational corporation that houses multiple brands.

- The bona fide brand (e.g. Nike, Dove, Patagonia…).

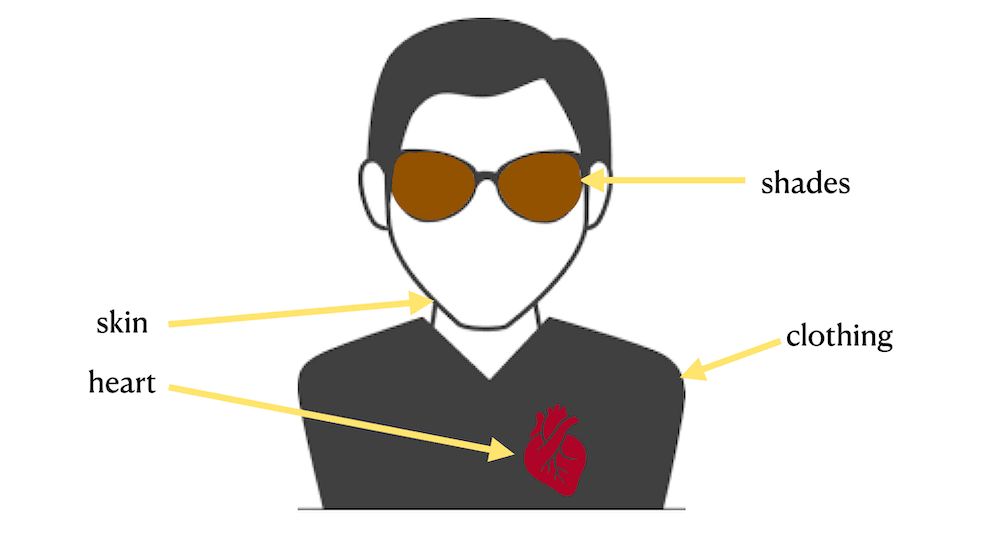

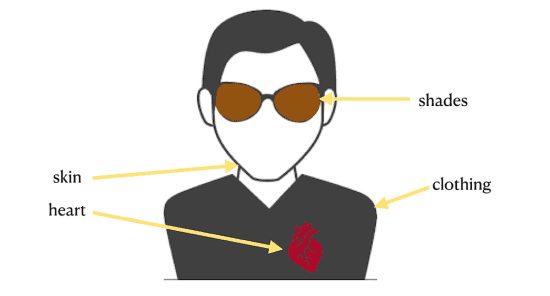

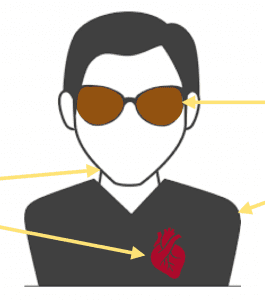

To put it another way, if I were to anthropomorphologize the notion of a brand, as in figure 2, I see four different levels or types of companies, only one of which represents being a bona fide brand. If I had to summarize the approach:

Branding, like beauty, is most powerful when it shines on the inside.#brand #beauty Share on XMirroring the levels presented in figure 1, the level 1 companies would be like the shades in figure 2. These companies — and there are millions of them — operate with little interest in or understanding of branding. They have no semblance or pretension of being a brand. They could be considered the most superficial of entities, just a covering, a filter. At best, the shades are their brand. This will include all those startups who’ve not concerned themselves with branding and/or marketing. There are also many look-a-like large firms that have made no effort to create a distinct and trustworthy entity, to wit the many firms with the rotating list of partner names on the outside door (e.g. your typical law or investment firms). They just become a haphazard string of initials. [N.B. As with every case, there’ll always be an exception that makes the rule].

#2 are the “clothing” organizations, like consultancies, or advertising agencies, that are selling to brands. They wear the clothes around the brand. They can help keep a brand alive, but the values and essence remain within the brands they service. NB Theses types of companies take on and remove clothing at will. For example, very few are prepared to reject a client based on ethics or principles.

#3 — such as a retailer or a corporate holding company — is the skin. These companies have or are the access to the inside (of a brand). They have the potential to be more meaningful and vibrant, but more often than not, they have intrinsic limitations. For example, as a distributor, they typically have razor thin margins. Corporate holding companies whose name isn’t also the commercially traded name are by definition removed from the customer.

#4, the brand, is like a human being, filled with organs and moving parts. Each brand has a unique identity and is made of the individuals that provide the service and drive the innovation. This is how and why the notion of a personal brand is at once a powerful and complex concept within a business. People don’t do business with a company, they do it with people. The key here is figuring out the overlap between the personal brand and the company brand.

The distinction of brand

So, what gives the brand a separate status as opposed to being merely a company with a trademarked name? A brand stands for something with values it upholds on top of providing value-added products & services. A strong brand does so differently from and better than others. Where many organizations (and weaker brands) lose the strength of their brand is when they try to be too many things to all people. Or, as in the case of a consultancy or communications agency, they are prepared to take on any client for the business. By association, an agency must be prepared to espouse the brand values of the customer it is servicing.

The more customer interactions are transactional, the weaker the brand is or becomes.#branding #brand #interaction Share on XTo sell a brand ≠ to be a brand

In a recent conversation about branding, I pointed out to a friend that the French language has a very useful word, une enseigne, that doesn’t exist in English. The word literally means a sign. In French, in commercial parlance, it’s typically used to describe a place where goods and services can be purchased. For example, an apothecary sign (or “apotheke”) or the green pharmacy cross establishes that ‘here is a chemist.’ Walmart or Carrefour are also ‘enseignes.’ As such, these two retailers exist as trademarked names. Their existence as brands is based on three principle things:

- the selection, price and availability of the brands they carry

- convenience factors (proximity, parking, etc.)

- the experience (i.e. the service inside and outside the store)

A retailer like Walmart occupies a place in the mind of its customers thanks to the service it provides. It is trusted to the extent it provides every day low pricing (EDLP). That alone is not enough to warrant being called a brand. A large part of the way Walmart lives in the mind of its customers is related to the selection of brands on hand. If the retailer sells Nike, Puma and Adidas, one could say that it then embodies a small piece of each of these brands. Accordingly, with the thousands of brands it carries, the Walmart brand is watered down. The appreciable value that Walmart provides is rather practical and very much related to price (as its corporate mission states). Of course, its 2.2 million employees attribute meaning to being employed at Walmart. But it’s hard for Walmart to say that, by itself, it stands for something important other than the convenience, selection and price. To wit, efforts to espouse political perspectives can be very tricky. When it sells so many brands and items, it’s a holding space and is obliged to want to please pretty much everyone. It can’t afford to stand up for a strong point of view. Amazon, the everything store by its own admission, has the same issue in spades, in that it lives principally through its website experience.

How can an enseigne become more of a brand?

Because retailers have access to the customers and own the sale (along with the personal data), they have a powerful asset. However, the relationship between retailer and supplier (i.e. brand) has seemingly forever been adversarial. To be a truly great brand, you need to be trusted up and down your value chain, including the relationships you have with all stakeholders. A true brand has a consistent ethical viewpoint and behavior that is lived inside and outside the company. These are fundamental to a brand’s essence. Where Havas’ Meaningful Brand survey includes a number of practical considerations and criteria (convenience, price, etc), I attribute a much lower value to such matters. Yes, convenience and price are relevant, but values and ethics are far more powerful indicators of the meaningfulness of a brand.

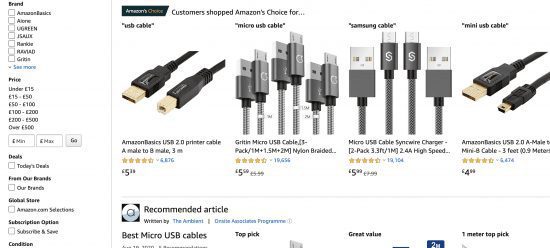

Amazon’s use of data to mastermind their own label products has been very effective, but it’s clearly at the expense of the brands. Just take a look at the search term “USB cable” in Amazon:

Another important facet for building a brand is the way the employees feel about their employer. As I like to provoke, how many of your employees would be prepared to get a tattoo of your company logo? A bona fide brand lives, first and foremost in the hearts and minds of its employees. This does not appear to be the case at Amazon and represents a second strike against them as a bona fide brand. This recent interview with Alex Kantrowitz of Tim Bray, ex-VP at Amazon, is quite a stinging and incisive review of Amazon’s internal culture.

Can own-label products convert to brands?

There are some ‘enseignes’ that become more like brands by virtue of the distinctive experience they provide. For such an experience to qualify as a brand, I would argue that it needs an element of exclusivity, such as you might get at Harrods or Le Bon Marché. It can also be because they start to carry a greater percentage of private label items. A case in point is Marks & Spencer where 99% of its items sold are own labelled. As such, I believe that these three “enseignes” have managed to craft legitimate brands.

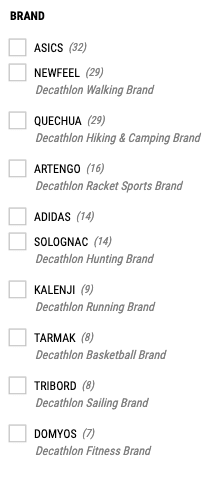

Another interesting example is Decathlon, the French sports retailer, that has gradually converted the majority (70% to 80%) of its sales to its own labels. However, its own label brands aren’t sold as Decathlon. At best, they might be Kalenji by Decathlon. As an example, here are the ‘top’ listed brands on Decathlon’s site for its men’s sports shoes selection. Only two listed below are non-Decathlon.

But here’s the rub. These Decathlon sub-brand names don’t have a heartbeat. Whenever I have spoken to a Decathlon store employee, I have never heard the slightest attention or affection for these own-label brands. Practical and pragmatic to be nice. Cold and ruthless to be factual. A brand — whether B2B or B2C — must be alive among the employees through to the customers.

Another feature of the way Decathlon has built these own-label brands is that, like Amazon, they were built off the back of legitimate brands that they carried, scrapping the sales data to know which shapes, colors, sizes, etc. are most popular and then, using its own manufacturing process to create their own-label items, thereby eking out considerably better margins. To be a good brand is to represent a sign of trust among all stakeholders. To be a great brand, however, is to inject meaning and value into all those who interact with it.

The making of a great brand?

In a follow up post, I’m going to explore how to go from being a bona fide brand to being a great brand. Here’s the short story:

A great brand lives within the minds of the employees, stakeholders and customers as a consistent and appreciable value.#branding #greatbrand Share on XThanks for having read all the way through. Please let me know your comments, thoughts or questions! What surprised you? What do you agree or disagree with?

—————–

***If you like my writing and are interested in fostering more meaningful conversations in our society, please check out my Dialogos Substack. This newsletter will feature articles on why and how we can all improve our conversations, whether it’s at home, with friends, in society at large or at work. Subscription is free, but if you see value in it, you are welcome to contribute both materially and through your comments. Sign up here: